08 March 2024 Marcin Dudek (*1979 in Krakow), works with installations, performances, collages, and archival images. His artworks explore themes like violence, subcultures, and the dynamics of crowds, often reflecting on his personal experiences within the hooligan scene in an autobiographical manner.

Can you tell us about your early life in Poland and how you became involved with the hooligan scene? What draws a young person into a group like that?

I grew up in a working class district south of Krakow, in a council estate called Wola Duchacka East, in the end of the 1980s. This landscape was quite rough, low income families struggling to meet basic existential needs. My mother was always busy trying to supply the daily meals for a family of six, so my siblings and I were raised by the streets. My older brothers were going to football matches, I started following them, and that's how I got involved.

Each neighborhood supports one of two football clubs in Krakow. Mine was KS Cracovia, which had a small but very loyal fan base. At a time when I lacked other forms of structure in my life, this tight-knit group was a shelter; after this rst introduction by my brothers, I became even more fanatical than them, going to every match, traveling all across Poland to attend the away games, collecting experiences of this collective.

What prompted your transition from being involved in the hooligan scene to pursuing art? What were the first touch-points you did have with art? What caught your attention initially?

This transition happened over the course of a few years, as the result of multiple factors. I was already interested in acts of creativity when I was spray-painting the neighborhood with symbols and signs of the local club, making flags in preparation of a match, participating in all of this visual paraphernalia which surrounds the games.

With time, I became less involved in these creative outlets of the club, and turned more into a violent participant of the group. When I was 17, one of my friends was murdered during a match, wearing a football scarf I had lent him. This tragic, pointless death led me to realize many things, about the fragility of life, what loss means, what danger we were putting ourselves in.

A few months later, right after I turned 18 (and could be tried as an adult), I was given probation for an offense, and started living under the constant surveillance of the state. This marked another step in the process. During this time, I was working at a big American printhouse in Krakow, packaging glossy big-name magazines in boxes destined for all of Eastern Europe. I became interested in these magazines, started reading them, especially a publication about painting, which became my gateway into art history. In the tiny, 10 square meter room I shared with my brother, I started drawing then painting reproductions of these artworks, realizing that I could transfer my skills from gra ti and signage into the creation of ne art. Over time, I started going to less games, diving more into this new activity, which appeared as a sort of revelation. I’ve made a few pieces about this process, including a recreation of the room where this transformation happened, which is called Head in the Sand.

You decided to study arts. How was your experience at art school? When did you start using the camera and what did you first take images of?

Art school was another world. My sister suggested I apply to art school in Salzburg, where she was living; it was a different country, a different language, a different environment. The location wasn’t important to me, so much as the escape from Krakow. I couldn’t really play the card of saying where I come from, but I could learn lots of new ideas and techniques. In this multiverse of experiences in Austria, I was able to take two years of photography classes with Michael Mauracher, who introduced me to the language of contemporary photography.

During this time, I took some images, but these were an escape from the past, completely unrelated to what I do now. Though I use many photos in my work, I am rarely behind the camera; I am interested in reconstructing the past through a photographic archive, with images that sometimes come from my own collection, but often are taken from news reports, police surveillance cameras, found footage online, or other fans’ photographs.

Your work involves different materials and mediums. How do you decide which medium is the right one for a project?

Photography is an interesting starting point for multimedia installations. In my work, I attempt to reconstruct the past, and I choose the medium in order to arrive at the most accurate representation of a particular moment in time. Photographs work as a memorandum, kicking off a chain reaction: from the image of a crowd in the terraces, I have a strong sensation of the moment, of the textile of the jackets, the smell of the smoke grenades. I can borrow from these associations to represent the experience, finding the material which is closest to the memory, reworking it in my collages and sculptures.

This is true both of photos from my own archive and of photos from historical events. Looking at images from the Heysel Stadium Disaster, for example, I feel a connection; there is something universal in the experience of real crowd violence. I use different mediums to confront and convey this human emotion.

Your technique of image transfer adds a unique layer to your works, often creating a tactile quality. How did you come upon this method, and what does it symbolize or add to the narratives you wish to convey in your art?

I was working with medical tape for a long time, attracted to this material for its association with the body, its surface which resembles skin, its importance in dressing injuries. When I started transferring images onto this surface, it brought this relationship between my work and the body to a new dimension. Suddenly, the images became like a second skin of memories, a tattoo inked onto this rough, corroded surface. This technique is very time-consuming, and while you do it, you really have time to take in the image.

I nd this process to be somewhat healing. The images I work with are often very di cult: remnants of a violent past, which I use to construct a scaffolding, a structure to hold the evidence of that moment. With images transferred onto medical tape, I recreate the moment as seen by the objective lens of a camera, then project the subjective lter of memory and experience onto it. Often, I do this by deforming the image, wounding the surface of the tape with a knife or torch. This destruction is meaningful; I abandon the clarity of the photograph for the energy of an internal image, turning fear and adrenaline and distress into a visual language. It is also a form of protection from images that possess something fatal in them. I am searching for the moment before death, the strange lucidity of that bodily experience, where the mind in danger experiences the loss of self.

The first time I showed any photographic material related to this subject was in 2013, in a show called Too Close for Comfort with Harlan Levey Projects in Brussels. There, I printed archival images 5mm tall, bringing the visitor in for an intimate look into the past I was just starting to explore. It took me 10 years to start speaking about my experience, and in the 10 years since, I have developed these techniques and this visual language to deconstruct my memories and make them accessible to others.

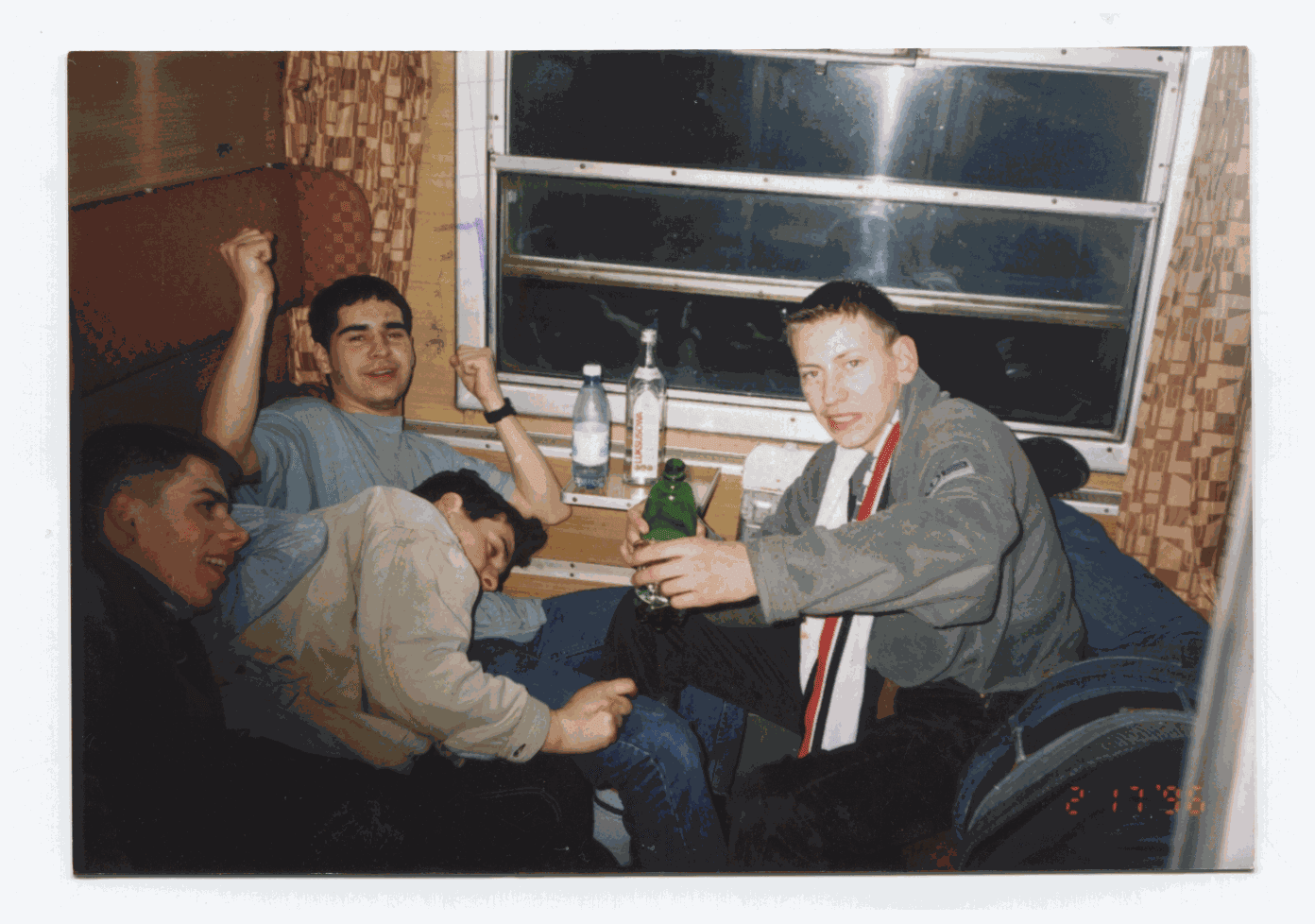

Marcin Dudek, Away Game, 1996 (from personal archive).

You work a lot with symbolism. Can you explain some of the reoccurring symbols, their significance, and their meaning to us?

Certain elements appear in my work again and again, across time and various mediums, though I don’t know if I would call it symbolism. The bomber jacket is one good example of a recurring image in my work. As teenagers, we adopted this piece of clothing because it was cool, in a collective decision to wear this military-style uniform, with its dark exterior and bright orange lining. This object was originally just a fashion choice, but as it became a part of our group identity, we gave it meaning. Much later, I began to unfold the layers of meaning in this jacket, using its image to channel its energy. As I worked, it became a shelter where I could hide and process all of these memories. It appears in various works, both in collage and installation, for example in the monumental textile sculpture The Group, where hundreds of jackets are sewn together to create an enormous shell which visitors can enter and experience. Though the image of the bomber jacket is evidence of a speci c moment in space and time, I believe it speaks to broader questions that are part of the basic human experience, thinking about the construction of identity, both as an individual and as a community.

Orange seems to seems to appear in many of your artworks. Why do you choose this color (e.g. smoke grenades)?

This color appeared organically in my work, as it did in my life. It is the color of the inner lining of our bomber jackets, as well as the smoke grenades that we used in the stadiums. We didn’t have a choice in the color of the smoke: we had access to these distress ares via people we knew who worked on boats, who would smuggle some of them to us. In the gray Baltic Sea, this orange makes you very visible; in the stadium, we used it as a screen of invisibility, hiding in the smoke, hiding in the crowd, sacri cing our individuality to the masses. It turned into the color of my performances, seeped into my work, but it is a completely apolitical choice, there is nothing speculative about it. This orange is the color of the neglected, and it came into my world by necessity.

How do you perceive society's draw to spectacle, especially violent or aggressive spectacles?

I think in a society that is suppressed by monotony, by the routine of the working class, there is a strong need for release, a drive to be fully yourself or to become someone else for a little while, which reaches extremes because the sense of frustration is also very high. This was the case in my experience: though it’s not a generality (some of the people engaging in this spectacle were from wealthier families), most of the youth were from really poor backgrounds, and were escaping this sense of oppression in sometimes unpredictable ways. There is something truly exciting, and very attractive, in this moment of collective celebration, which is also a drive for self-destruction.

You work a lot with archival material. How do you involve the use of photograohy in your practice and where is the archive material from (e.g. surveilance camera images)?

Photography exists in my work as one among many materials which allow me to revisit the past. One of my collages, 5 Seconds, speaks to this point: in 1993, I was able to attend a national match for the rst time, Poland vs. England, inside what used to be the largest stadium in the country. During this match, chaos unfolded – Polish fans fought amongst themselves and with the police, at one point the police were even forced to retreat from the stadium by hooligans who ripped benches from the oor to use as weapons. In 2018, 25 years later, I started obsessively looking for all possible evidence of this event, searching the national archives of Poland for images from the police and the press. Finally, I found 5 seconds of video footage from Polish national television. This sequence appeared to me as the most important, vivid artifact of this match. I built a composition around stills from this footage, constructing a whole architecture of memory from every possible evidence I could find of this event: tickets, blueprints, sound waves of the crowd, testimonies of other fans published in the football fans’ zines, photographs of banners, photos of the benches, stones, and concrete pieces used as weapons, colors of the clubs, pre and post-match photos, etc. In this way, the ve seconds of footage became the foundations for an enormous forensic theater, similar to a control room at the police station.

In addition to this extensive process, I sometimes include personal images, both from my own archive (if I was lucky enough to have a camera at the time), and pictures I’ll take while traveling to a place in the course of my research.

What would you hope others feel when they see your art?

Behind my work is the drive to transmit the complexity of human emotion, and serve as a reminder that every choice we make has consequences, even if it happens in the blink of an eye, it carries on as a scar in our brains. I try to confront these enormous, intense subjects drawn from my lived experience, and offer them to the viewer in an intelligible, sensible form.

Can you give us some insights into what you are currently working on? Are there any subjects or mediums you'd like to explore in the future?

At the moment, I am exploring a new area of my work through a residency called ReSilence, an initiative by the European Union with S+T+ARTS. This year, I am working with OOF Gallery and the Tottenham Hotspurs Stadium on a portrait of the stadium through sound, recording both the cheers and chants of the crowd and the vibrations of the infrastructure. I will be showing the result of this collaboration in London in November at OOF Gallery, which is within the walls of the stadium itself.

This year, I am also continuing a series of works I call “memory boxes”, installations which recreate spaces from my past, which transmit the emotion of the moments which happened inside. In May I will have a solo show at Leto Gallery in Warsaw, where I will be installing a very speci c type of jail cell, “izba wytrzeźwień”, known to English speakers as a drunk tank. This is where Polish police put intoxicated people, leading to at least a few hours of incarceration, if not several days, and a very expensive ticket on the way out. I’m interested in the idea of intoxicated people dreaming inside of these cells, living a process of transformation as they sober up, seeing themselves from the outside, analyzing the trajectory of their life.