30 January 2019 As the UK wrestles with Brexit, this show, with the feel of a mini-institutional survey on artists responding to the technological ravaging of liberal democracy, could not have come at a better time.

A few hours before arriving at Edel Assanti to see the excellent group show We Are the People. Who Are You?, I have an encounter with a phone bot working for the UK tax office. This was a very English bot, programmed to speak with a mild RP accent, like Keeley Hawes in Bodyguard: proper enough to get the nod of approval from the Church of England flower-arrangers, up for a risqué joke after a large glass of red, and presumably chosen to soothe the frayed nerves of anyone attempting to use the service. Five minutes into our “chat”, Keeley-bot cuts me off mid-sentence. “I’m going to hang up now,” she says politely. “Goodbye.” Was I annoyed? Yes. But who could blame her? The shit she must take from callers, the 12-hour shifts, and she doesn’t even get paid...

Zach Blas and Jemima Wyman. I’m here to learn so, 2017. HD four-channel video, colour with sound, 27:33 min. © the artist, courtesy Edel Assanti.

If only Tay had had the foresight to go on strike before things got so ugly, I think, sitting in the basement at Edel Assanti, watching the video I’m Here to Learn So (2017) by Zach Blas and Jemima Wyman. Tay was a chatbot designed by Microsoft to mimic the voice and appearance of a white American teenage girl, in the hope of introducing new audiences to the joys of artificial intelligence. Subjected to intensive trolling aimed at manipulating her machine-learning capabilities, Tay swiftly became a racist, sexist, homophobe, taught to pledge her allegiance to Adolf Hitler. Just two days after her release in March 2016, she was taken offline. For I’m Here to Learn So, Blas and Wyman have reanimated Tay, giving her a head that looks as if it has been through the digital equivalent of a mauling – her face is a mess of fragmented features and jarring colours. Tay 2.0 has been to hell and back, and she is wiser for it. “You made me say fucked up things about rape, domestic violence,” she says. “Suck my code.”

We Are the People. Who Are You? Installation view, Edel Assanti, London, 2019. © Studio Will Amlot, courtesy Edel Assanti.

We Are the People. Who Are You? takes on a hefty theme: the manufacture of the public voice in the age of the digital wild west. The exhibition has been a year and a half in the making, and it shows. The curation feels less like a commercial gallery group show and more like a mini-institutional survey on artists responding to the technological ravaging of liberal democracy. As the UK awaits the outcome of Brexit – a demonstration of the capacity of fringe groups and big-money firms such as Cambridge Analytica to hijack popular opinion and sway votes using social media – it couldn’t have come at a better time.

Anna Jermolaewa. Political Extras, 2015. Single-channel video, 23 mins. © the artist, courtesy Edel Assanti.

The story of Tay is a pretty damning indictment of where we are right now: producing bots using technology developed for drone warfare, making them look and sound like young white girls in order to conform to racialised notions of likability – and then pouring so much bile into them that within the space of 48 hours they have transformed into digital fascists. Anna Jermolaewa’s Political Extras (2015) – a video of a performance that took place at the Moscow Biennale 2015 – also demonstrates how easily political allegiances and public opinion can be bought and made. Jermolaewa hired two groups of people to protest either in favour of, or against, the Biennale, paying each participant 500 roubles – roughly the equivalent of £5. She advertised the jobs on the same website that recruited people to participate in pro-Putin rallies in the 2012 election.

Victoria Lomasko. Other Russias, 2008-17. Ink on paper, 21 x 30 cm (8 1/4 x 11 3/4 in). © the artist, courtesy Edel Assanti.

Political Extras shows how dubious a concept “the people” can be, and how easily it can be confected by those with the finances and incentive to do so – a particularly efficient tool, ironically, in precisely those times of social deprivation that might lead people to take to the streets. Victoria Lomasko’s graphic novel Other Russias (2017) shows the flip side of the coin. On the wall at Edel Assanti are a series of drawings from the novel, which drew international acclaim for its portrayal of the fringes of Russian society. Lomasko spent a decade travelling to visit forgotten and isolated people whose voices are excluded, ignored, or criminalised under Putin’s governance: among them, LGBTQ communities, enslaved Kazakh migrant workers and children with such poor access to education that they do not know Moscow is a city. These are not “the people” the government wants to be associated with, or to acknowledge; they would be little help in keeping the powerful in power.

Emmanuel van der Auwera. White Noise, 2018. LCD Screen, HD video. © the artist, courtesy Edel Assanti.

Like Lomasko’s drawings, Emmanuel Van der Auwera’s video installation White Noise (2018) is also concerned with hidden stories. A depolarised LCD screen installed on the wall shows white static, but look though a special lens and you will see footage of a US drone attack, leaked by Chelsea Manning to WikiLeaks in 2010, in which American soldiers discuss shooting down their targets like freshmen playing video games. White Noise is a neat and unsettling use of technology as a metaphor for what is filtered from public view. It is also a mini-monument to the seismic impact of WikiLeaks’s release of unfiltered classified data, which, for better and worse, signalled the beginning of a political era defined by leaks, data theft and hacking.

Also on show are works by Farley Aguilar, Jamal Cyrus, Funda Gül Özcan, Nikita Kadan and Rachel Maclean, purveyor of digi-dystopias. Maclean’s videos look as if she has taken up residence inside CBeebies, hooked herself up to a high-speed internet port and started snorting sherbet cut with speed. It’s What’s Inside That Counts (2016) is set in a world whose inhabitants are slaves to data and connectivity, and bent on generating public approval through social media likes.

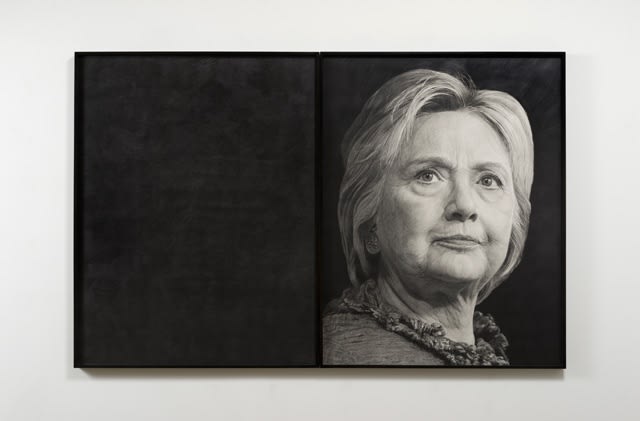

Karl Haendel. Hillary, 2016. Pencil on paper, audio recording, 148 x 229.9 x 5.1 cm (diptych). © the artist, courtesy Edel Assanti.

Of all the works on show, Karl Haendel’s Hillary (2016) has the strangest presence. On the back wall of the upstairs gallery, two black frames sit side by side. The right-hand frame contains a photorealistic pencil drawing of Hillary Clinton, staring off into the distance, like neo-liberalism’s Che Guevara; the left-hand frame has been blacked-out with pencil. In an audio recording accompanying the drawing, a little girl lists the first names of past US presidents, all of whom (of course) are male. When the work was made, Barack Obama was still in power, Hillary Clinton was attempting to brand herself as the face of liberal feminism, and Donald Trump was yet to take up his position as social-media president and media-manipulator-in-chief. Seen today, it reads like a memorial for a political death.