06 May 2017 Born in 1978 in Serpukhov, a small town near Moscow, Victoria Lomasko is an accomplished artist and graphic journalist who published her first book, The Provinces, in 2010, and her second, Forbidden Art, in 2011. Dedicated to the events surrounding a controversial 2006 Moscow art exhibition of the same title, Forbidden Art was translated into French and German. Other Russias, Lomasko’s latest publication, is the first to appear in English (with text translated by Thomas Campbell).

This beautifully produced book is a 320-page anthology of her graphic reportage from 2009 to 2016. It paints a collective portrait of Russia’s others — ranging from school children in desolate villages to inmates in provincial jails, ethnically Russian sex workers in Nizhny Novgorod to Central Asian slaves in Moscow. Paradoxically, the book’s greatest merit for non-Russians interested in contemporary Russian culture may be the fact that it is oriented toward an internal audience — perhaps one as small as the artist’s own circle of friends. Leafing through a work that looks like a personal sketchbook produces a sense of intimacy, and makes Lomasko’s social criticism feel more like a personal commentary on Russian reality than political discourse.

The genre of graphic reportage is deeply rooted in the Russian tradition. A subgenre of comic journalism, it was frequently used in the USSR in extreme situations, when no other technology was at hand — for example, on the front in World War II or during the Siege of Leningrad. For Lomasko, this genre allows her to document scenes where news cameras aren’t allowed, like polling stations or court proceedings. In these cases, Lomasko’s very use of the genre is a commentary of state censorship.

Other Russias is organized in two parts: “The Invisible” and “The Angry.” Indeed, binary oppositions frame the book. Lomasko plays with quintessential oppositional archetypes like Westerners and Russophiles, Revolutionaries and Orthodox believers, city and countryside. Through it all, one of the core oppositions is masculine and feminine. Lomasko, who is known for her feminist activism, engages with her male and female characters differently. With the exception of a strictly documentary report on an adolescent penal colony, Lomasko’s men fit more archaic, distinctly Russian archetypes. The series titled “Black Portraits” presents a curious trio: a Russophile (the stonemason Sergei, an Orthodox activist), a Westerner (a professor at MGIMO, the Moscow State Institute of International Relations), and a “superfluous man” (a young adult of humble origin mourning his father’s death). It is up to the reader to figure out the relationship between the three: which father figure would the raw youth choose?

Lomasko’s archetypes are instantly recognizable to Russian readers, tapping into the post-Soviet popular imagination. Compare, for example, the portrait of a lecturer at MGIMO (one of the most prestigious schools in Russia), with a painting by the beloved Russian primitivist artist Vasya Lozhkin (b. 1976), titled Life Without a Beard (year unknown):

Both pieces mock Russians who believe themselves to be “Westerners,” but while the influence of the West in Lozhkin’s painting is allegorized, Lomasko presents it in realist terms. The author goes so far as to name the person, his job, and even the hospital where he was born (a jab at the detail-heavy style of the typical 19th-century Russian novel). One can only wonder about the legal repercussions of this portrayal. Everyone else in the book is identified only by first name.

Lomasko’s coverage of the adolescent penal colony is based on her volunteer experience giving drawing lessons to the teenagers behind bars. The picture of the author and her students is the only photograph in the collection:

The purpose of these drawing lessons is art therapy, a practice in which Lomasko firmly believes. It’s fascinating to see the images these teenagers produce: religious iconography, abstract expressions of anger, cartoon characters from their childhood. Once again, Lomasko doesn’t preach: “Drawing Lessons at a Juvenile Prison” makes no grand statements about Russian jails and how to reform them, but rather documents the modest contribution of a single person.

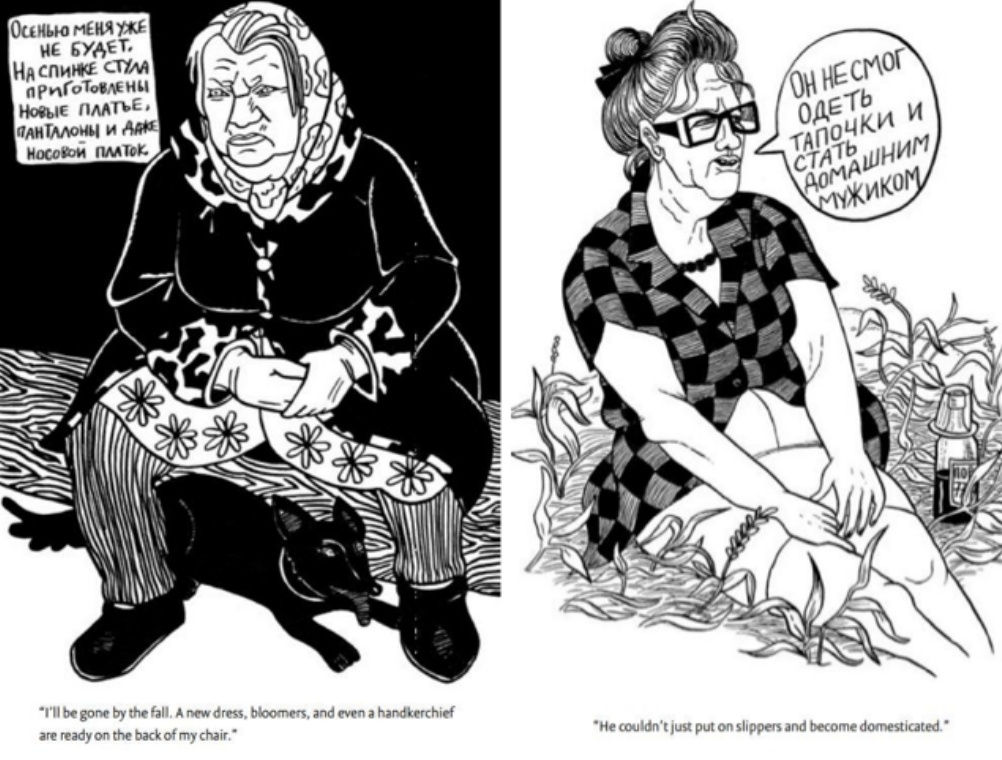

The female portraits of Other Russias offer an especially nuanced perspective on old age, prostitution, gender imbalance, and alcoholism. Lomasko avoids the usual traps of representing sex workers as either the soul of “Mother Russia” or as an axis of its social ills (“women with low social responsibility” is a recent viral euphemism in Russia, drawn from Vladimir Putin’s sarcastic reaction to the scandalous revelations in the “Trump dossier”). A somewhat peculiar feature of these drawings is the artist’s fixation on underwear. By drawing half-dressed mature women in suggestive poses outdoors, Lomasko subverts representational taboos and makes another implicit comment on the body politic, alluding to the 2012 ban on lace underwear imported from the West.

At a personal level, Lomasko’s drawing of an old lady saying that she has prepared her funeral clothes instantly reminded me of my own grandmother and the death preparations she rehearsed throughout my childhood: “This is what I want to wear to my own funeral.” I’m sure I’m not the only Soviet-born reader for whom this image hits close to home.

At the same time, the old women in Other Russia have a distinct political voice — or rather, voices: they recite Pushkin’s poetry in the Moscow subway, worship Lenin’s statues on the streets, make snide remarks about prayers against the authorities, openly support Pussy Riot, and even go as far as declaring their wish to assassinate Putin. There is a deep realism in these portraits, both at the graphic and textual levels.

The same can be said about the representation of sex workers in Nizhny Novgorod. They are not depicted as victims, but as participants in a capitalist economy; they are aware of their condition and already have models for transitioning to a different job. What is missing, though, is an acknowledgment of the professional hazards and traumas of sex work. Without this acknowledgment, it is impossible to develop narratives of healing and recovery after sexual abuse. That narrative is entirely missing from Russian culture, and from Other Russias as well. Instead, the book wryly articulates the feminine condition as a display of professional pride — with bittersweet notes of revenge: “Some clients ask me to piss on them, but I’d be happy to shit on them on behalf of all women.”

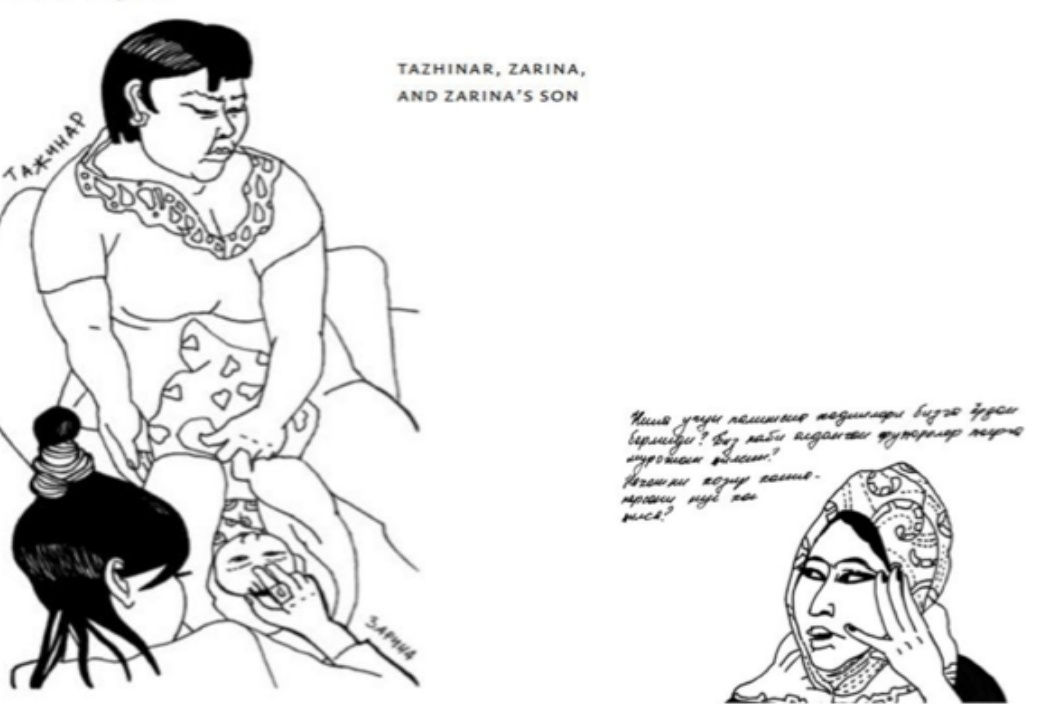

Another type of Оther, situated even lower on the social ladder than provincial sex workers, are “guest workers,” ethnically non-Russian people who migrate to Moscow from former Soviet republics in search of work. Usually settling in ethnic enclaves, these “guest workers” — who are actually permanent residents — have become a part of the urban landscape in central Russia. There is a hierarchy among these ethnic minorities, based on their place of origin, gender, occupation, and ability to speak Russian. Some own businesses (often illegal) and are integrated into corrupt economic structures, while others are enslaved by their patrons. Lomasko’s interest in the problem of modern slavery stems from her work with human rights organizations. She presents the stories of freed slaves from Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan in a detached, objective manner. With the exception of one speech bubble in Uzbek, the immigrants’ speech is rendered in grammatically correct Russian. The Russian and Uzbek texts state the same grievances: “Why do the police not help us? Where should people like us complain? Is it all about money these days?” Lomasko also focuses on the issues of rape and unwanted pregnancy. One of the most powerful images shows a woman giving birth to a child who will either be sold or raised as a domestic slave. In one way or another, mother and child are usually separated. One such mother, a freed slave whom Lomasko interviews, reveals her dream to see Paris and the United States. The narrator remarks: “Under the existing system, migrant workers are destined for slavery in one form or another, not for trips to Paris.” As in the case of the Nizhny Novgorod sex workers, Lomasko’s sober analysis of socio-economic factors overshadows the psychological issues of trauma and the possibility of future rehabilitation.

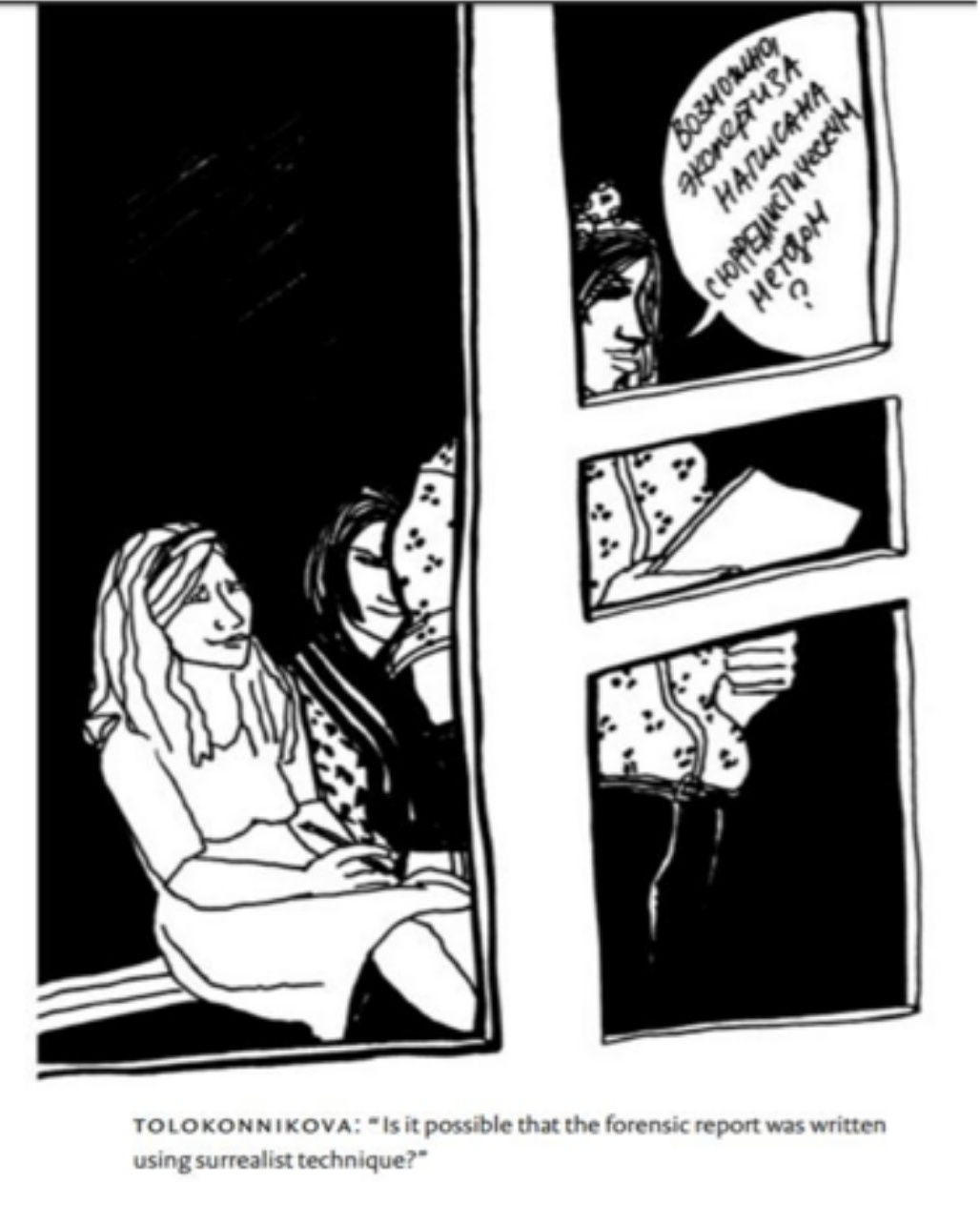

In the second section of the book, “The Angry,” Lomasko’s focus shifts to her own community of activists. Here, she chronicles the protests that erupted in 2012, when Vladimir Putin was elected president despite documented election fraud and massive oppositional rallies across the country. Lomasko, a participant in the protest movement, offers unusual insights into its key events: the Pussy Riot trial, the Taisiya Osipova hearing, the White Circle flash mob, the Pushkin Square Rally, the Bolotnaya Rally and the subsequent arrest of Mikhail Kosenko, Occupy Abay, Occupy Barrikadnaya, the two Marches of the Millions, and the murder of Boris Nemtsov. For example, in depicting the Pussy Riot trial, Lomasko lingers on its less significant moments, such as the breaks between courtroom proceedings. This allows the reader to feel what it was like to witness the trial first-hand, and to identify with the distress of the defendants, who were denied the right to use the bathroom. Importantly, the depiction of the Pussy Riot members is deliberately crude, highlighting the fact that beauty isn’t at issue in this conflict. Lomasko’s portraits stand in stark contrast to the sensual gaze that characterizes recent media coverage of Nadya Tolokonnikova, Pussy Riot’s breakout star.

Contemporary Russia is a confusing and dangerous place, where organizing an LGBT festival is akin to “running a military operation,” and where the word “activist” applies both to the left-wing opposition and to the nationalistic youth groups who commit hate crimes against them. By the end of 2014, the wave of large protest actions had abated, civil freedoms had been severely limited, and many key opposition figures had emigrated to the West. 2015 and 2016 were years of smaller local rallies: marches for science, education, and healthcare; the defense of Moscow’s Torfianka Park against plans to construct an Orthodox church in its place; and a strike of long-haul truckers in the city of Khimki. Lomasko’s coverage of these events demonstrates how grassroots activism continues to draw people into the protest movement and galvanize society; such smaller, community-based initiatives may become the future resistance platform.

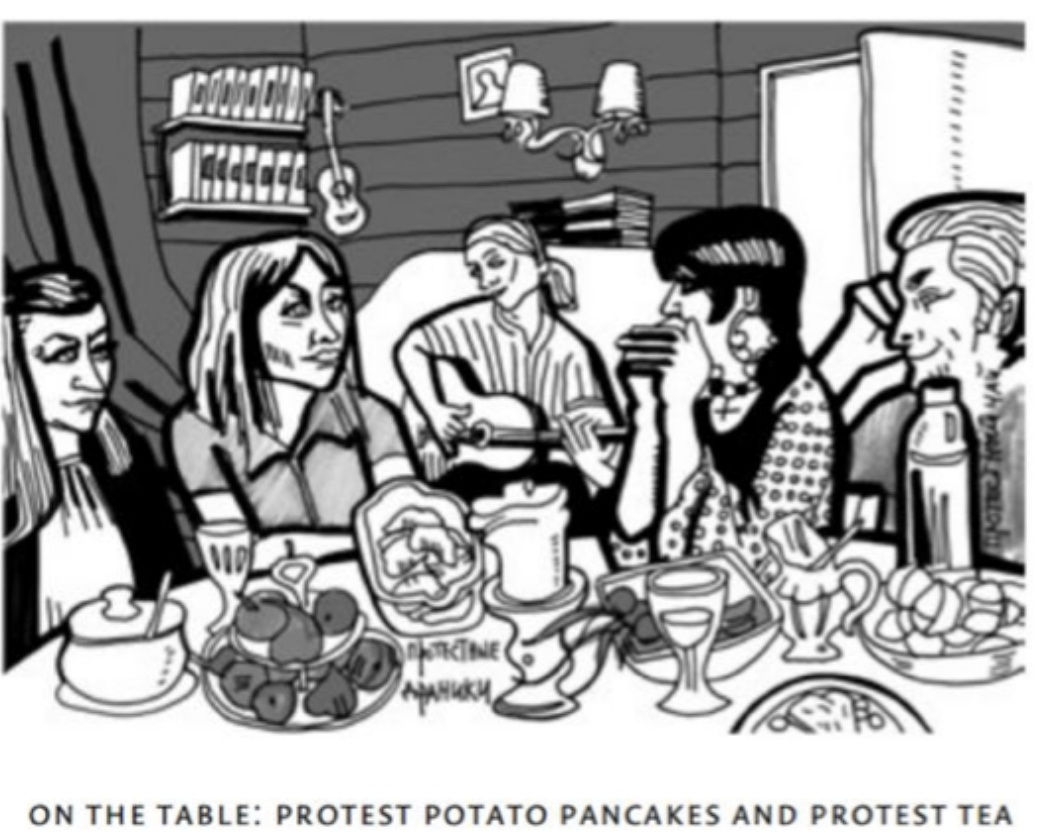

The last drawing in the book is of a humble communal table at a Khimki protest camp, an almost biblical scene: splitting protest pancakes and communing over protest tea. The Khimki camp united the liberal intelligentsia with the working class, Muscovites with people from the provinces, and ethnic Russians with non-Russians. It is in such places that the new civic identity of Russia must be born. With the publication of Other Russias in English, the still faint voices of this new civil society can now be heard in the West. At a time when most media coverage of Russia boils down to “the Russian mess,” Lomasko shares the valuable experience of resistance and resilience that has characterized life under the Putin regime for the past five years. Examining the political momentum following the Russian elections of 2012, we find many lessons relevant to our own political situation:

I think that many people were so excited to be in the throng of the 100,000-strong demonstration — and so impressed by the beauty of marching under multicolored flags — that they stopped critically evaluating what was happening.