08 April 2022 Interview with the Russian artist in exile Victoria Lomasko, whose drawn reports examine Putin's Russia and give a voice to those who never had it.

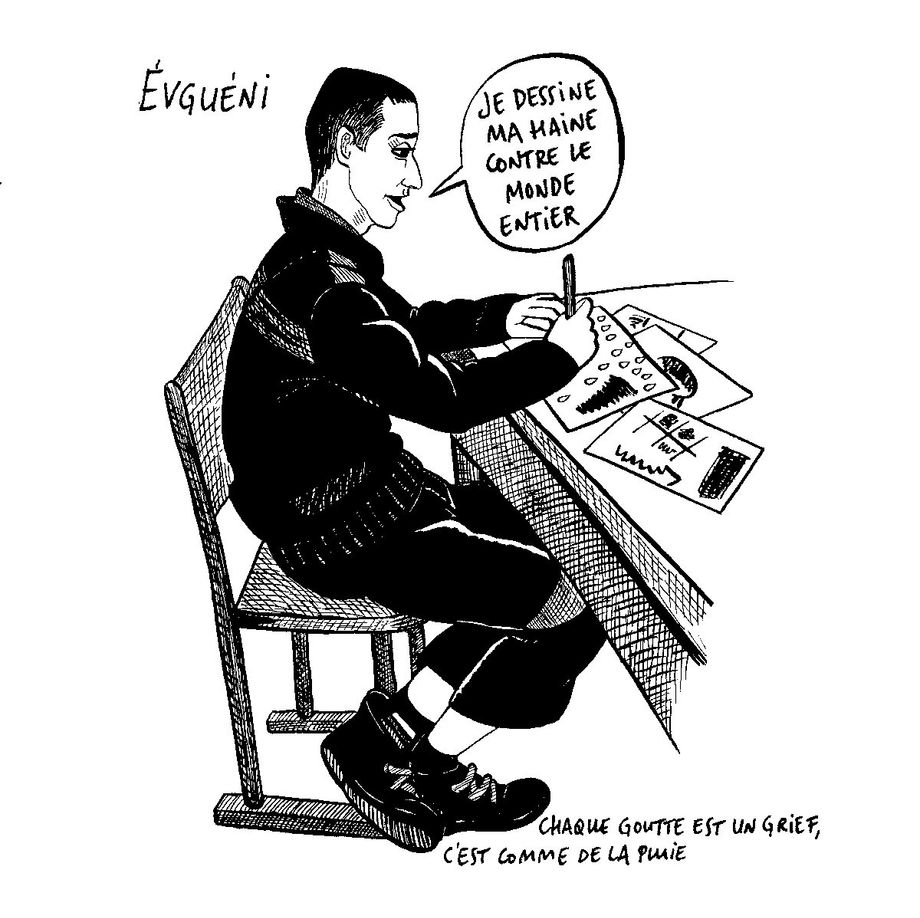

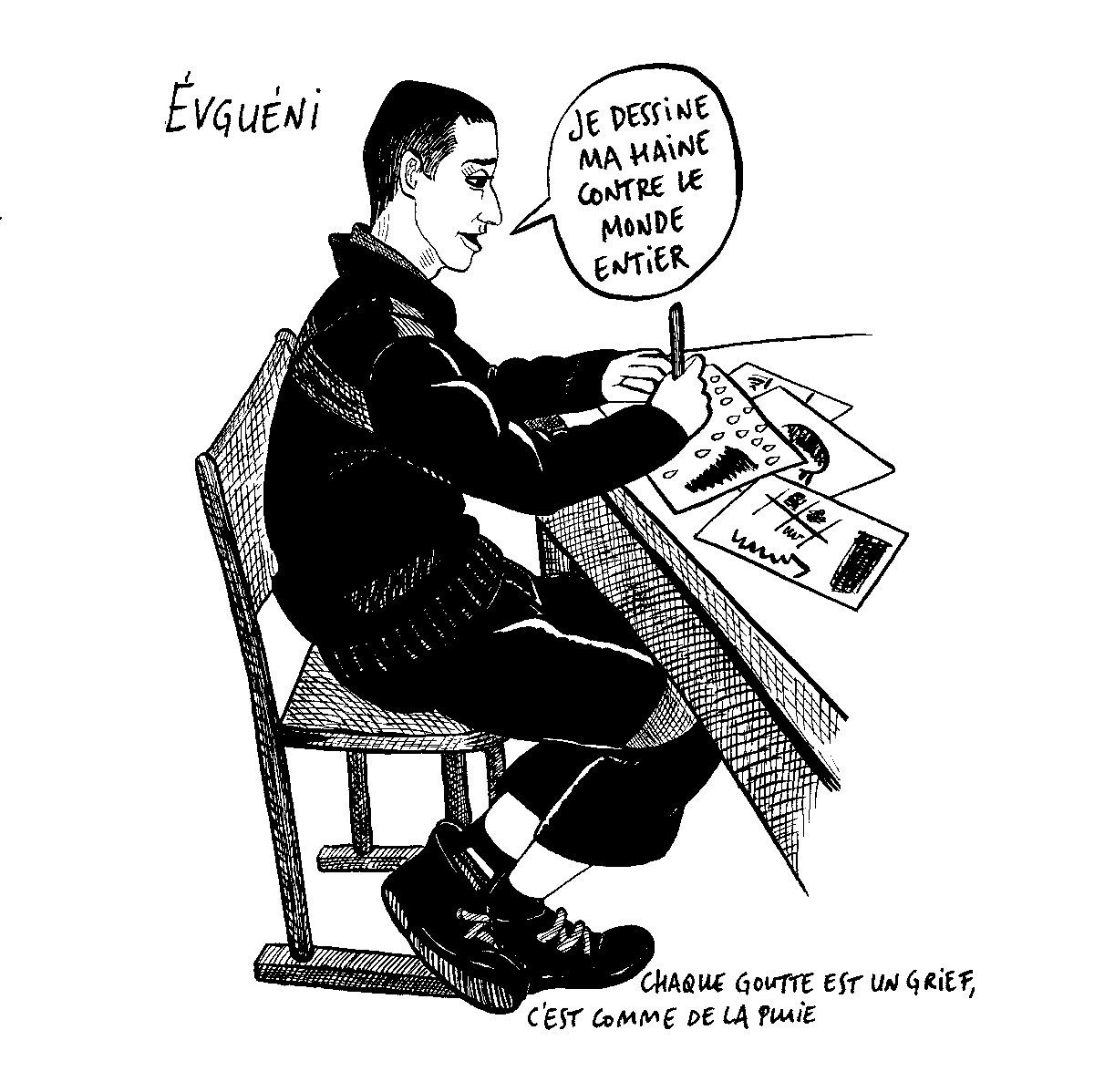

Voices that take you by storm. Unexpected. Often confused. Or angry. There is the former homeless teacher with a sad, distraught look: "My son took over my room in the barracks and said: 'Go away, I want to drink freely'. A teenager scribbling in a drawing workshop in a prison colony: "I draw my hatred against the whole world. The sex workers in Nizhny Novgorod laughing: "We're holding it together with laughter - and vodka. Or the 73-year-old crab-hooded protester, who is fired up: "Bravo, Pussy Riot! I would have sung with you: "Holy Virgin, drive out Putin!

These voices are the soil from which Victoria Loumasko draws her graphic investigations. Other Russias, a collection of reports drawn between 2008 and 2016, paints a portrait of a Russia that is anything but monolithic, plagued by misery and chaos. The book followed his report on the ubiquitous trial in 2006 of the organisers of a scandalous exhibition, Forbidden Art, which nevertheless showed a certain pugnacity of the Moscow art scene despite the repression.

That seems far away now. And Victoria left her country in a hurry after the invasion of Ukraine. So it was from Brussels that the woman whose books have never been published in Russia answered our questions, and who will soon be releasing a new book in several European countries entitled The Last Soviet Artist.

Victoria Lomasko, illustration from Other Russias, 2017.

You recently left Russia. Did you feel directly threatened?

"What threats did I face specifically? That's the question I've been asked in every interview in recent years. Unfortunately, I can't entertain the Western public with stories like Pussy Riot. I have not been in prison, I have not been searched or interrogated.

As an artist documenting reality, I used a different strategy: to be as discreet as possible so that I could continue my work over the long term. Three years ago, I asked a lawyer what would happen if my book Other Russias - which has been translated into six languages - was published in the country. He told me that it violated the new repressive laws so much that the possible publisher and I would face up to ten years in prison. Knowing this, I stayed in Russia anyway and made new works that scrutinise and criticise the Putin regime. But it was impossible to show this kind of thing in Russia. So they were only published and exhibited in the West.

Even without the war, I would have ended up on the list of "foreign agents" sooner or later because of my activities. Today, this list has been replaced by the list of 'national traitors'. Criticism of the regime, collaboration with Western organisations or opposition to the war in Ukraine are now serious crimes in Russia.

When I realised that the borders were almost all closed and that inside the country a big cleansing of dissidents was taking place, I bought a plane ticket to Kyrgyzstan - I had no visa or money to go to Europe. On the day of my departure, one of the foreign institutes I had been working with before the war suddenly got me a Schengen visa. And here I am!

In Other Russias, you describe what you call the "invisible" - people living in the provinces and often abandoned to their fate...

"I did the reporting on the 'invisibles' between 2009 and 2012. It was the time of the pseudo 'Putin stability'. Everything seemed to be going well in the country, liberals and contemporary artists in Moscow were living happily and full. But as soon as you left the capital, the poverty and arbitrariness were obvious. I was born in a small town and my parents still live there. I have known this precariousness since my childhood and I was interested in depicting it.

The nightmare that Russia is currently experiencing is not because Putin has suddenly gone mad. Arbitrariness was already everywhere. The situation has only worsened, slowly at first, then more and more rapidly. Today, Russia is 100 per cent a dictatorship.

Other Russias refers to the popular mobilisations of 2012, especially for free elections. What is left of it?

"The big demonstrations of 2012 took place only in Moscow. They were mainly attended by intellectuals and the middle class, for whom Russian society was a society where we could, like in Europe, defend our rights peacefully. They ended up in court for dozens of protesters. After that, people close to the opposition started to flee Russia. In 2021, a foreign journalist exclaimed, seeing me drawing a modest political action: "Oh, you're still here? It's good that at least one person stayed in Russia!"

And now, as you can see, I had to run away too. Those who stayed know that they will probably get a prison sentence if they take part in anti-war actions. Most people are convinced that in case of a mass riot the authorities are ready to shoot the crowd.

Your books mix graphic design and a form of journalism based on testimony...

"The first texts that appeared in my drawings, in 2008, were the characters' lines, quoted literally. I have always been interested in what people say, their opinions on life and their destiny. But at first my texts were very short, as comments to the drawings.

Later I started to study and use some journalistic techniques, like collecting materials and conducting interviews. In the last two years I have moved on to a new stage for my next book, The Last Soviet Artist, where I felt like writing more like a writer. I seem to have achieved this in the last chapter, titled "Moscow: Life on an Island". In it I tell how my friends and acquaintances, artists and activists, are trying to do something new and beautiful, important and useful, in this country where many things are already forbidden. I will never accept that their efforts, our efforts, were in vain just because a dictator started a war.

Like Other Russias, this new book is divided into two parts. The first part tells of my travels in the former Soviet republics. The main themes are civil society, activism, transformations of urban space, women's and LGBT rights, religion. The second chapter consists of three chapters: "Journey to Minsk", "Moscow: the Battle of Generations" - which deals with the demonstrations in support of [opponent] Alexei Navalny and the ideological conflict between young and old - and "Moscow: Life on an Island" - which evokes social life in Moscow on the eve of the war. You could say it's a final farewell to the Soviet era."

Do you think you can go back to Russia one day?

"Yes, without a doubt. The Putin regime has no future. This power will probably destroy itself - there have already been reports of arrests in the FSB [Russian intelligence]. My books will be published in Russian and the younger generation will read them. But in fact, I would prefer to be a citizen of the world, to live where I want to live when I want to live, to travel a lot and to show my work all over the world.

Translated from Russian by Gérald Auclin