Sheida Soleimani speaks the language of birds, deftly contorting her lips and breath to recite lilting sounds with distinct avian fluency. As far as the Iranian American artist is concerned, it’s her second language after Farsi. “Before I could speak English, I used to listen to bird sounds on tape,” says Soleimani, 32. She would spend hours playing recordings in her childhood bedroom, specifically bird sounds from North America. “I didn’t really have friends at the time,” she adds.

Soleimani, the daughter of Iranian political refugees who settled in what she calls the “corn and soybean world” of Loveland, Ohio, now lives in Providence, R.I., where she is the city’s only registered wild bird rehabilitator. When I visit her in May, she’s in her whitewashed brick basement — newly transformed into a bustling wildlife clinic — and using the sounds of a Baltimore oriole to soothe a Quaker parrot flitting inside a wood and mesh cage. The lime green bird, its wings sheared, had been dropped on her doorstep. “Whoever clipped the wings did a hack job,” she says. The rest of the room brims with other birds in her care, including robins, baby starlings, wood ducklings, mallards and two owls — an Eastern screech and a barred. There’s even a bunny that was found in a park, severely emaciated.

At the height of summer — peak bird season — Soleimani might have over 20 birds a day left by strangers on the porch of her black 19th-century Victorian home with cerulean trim. (“The most that have been dropped off on a given day is 29,” she says.) She also runs a studio out of her house, where she makes photo collages with hyper-saturated color and grimly satirical takes on geopolitics.

“I layer things and I construct things, and I do that to obfuscate and confuse, to make people spend time unraveling or taking apart the work,” says Soleimani. “There are a lot of languages and codes that might not be visible to the viewer, but I don’t think they have to be.”

She spends much of her time here moving between the clinic, taking in and feeding the birds, and the studio, which is in a garage behind the house. Her recent project, the Ghostwriter series, part of which is on view at Providence College Galleries, “aims to work out the relationship between the two most important care-taking practices in my life: my work as a wild animal rehabilitator and my work as an artist,” explains Soleimani.

In Ghostwriter, she turned the camera toward her father and mother, from whom she initially learned to rehabilitate birds. It’s also the first time her work directly addresses the personal histories of her parents, whose final years in Iran were defined by the staggering series of political ruptures — including a deposed shah and the subsequent Iranian revolution — that transformed the country in the late 1970s and altered the couple’s fate forever.

The two first met in 1975 at a hospital in Shiraz — he was training to be a doctor and she a nurse. They were also pro-democracy activists who together set up field hospitals for guerrilla fighters and Kurdish rebels. Because her father opposed Ayatollah Khomeini’s rule, which, Soleimani explains, put “a bounty on his head,” he was forced into hiding before fleeing on horseback over the serrated Zagros Mountains, first to Turkey, and eventually to the United States. Her mother endured nearly a year of solitary confinement in Khoy prison before she left the country and was reunited with him.

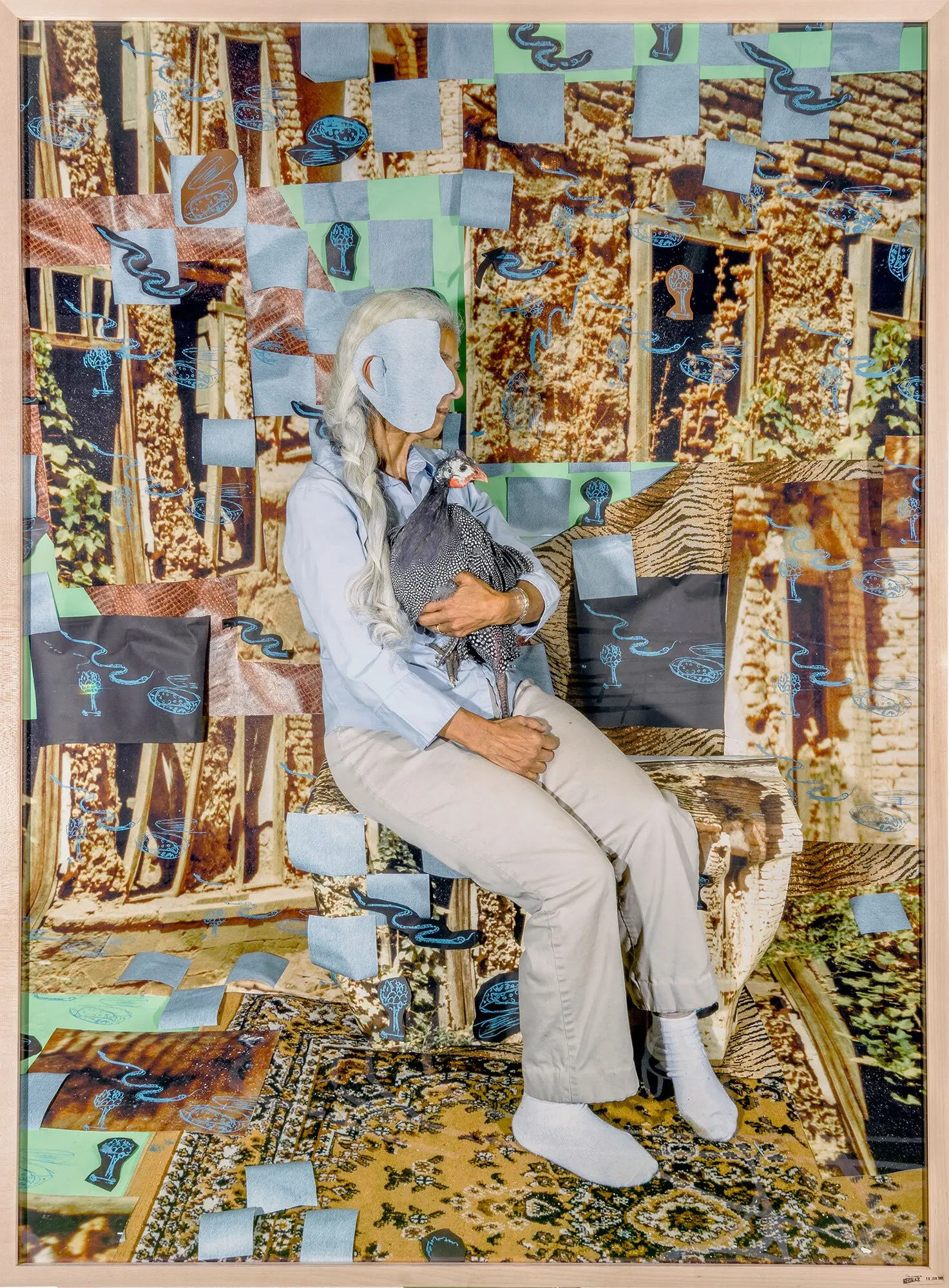

In Noon-o-namak (bread and salt) (2021), one of the central photographs in Ghostwriter, Soleimani’s mother poses for her daughter, her long white hair loosely braided and her face obscured by a piece of paper the artist cut and hung onto her ear to maintain anonymity on account of her status as a political refugee. In the background, a kind of patchwork of inkjet prints, some depicting her mother’s childhood mud-brick home, mix with screen-printed snake drawings, done by the artist’s mâmân, as Soleimani calls her mother. Close to her chest, and with a gentle maternal grip, Mâmân holds a guinea fowl, a type of bird she cared for in Iran.

“When birds have appeared in my work before, they have only come in as actors and signifiers — archetypal symbols of peace, war, death and horror,” says Soleimani, who sees a relationship between her rehabilitation of birds and her care, through her art, for people “abused by corrupt governments.” But she also sees the subjects as importantly distinct. And “in this new work,” she adds, “I want to use birds not as anthropocentric symbols but as routes to more vulnerable, attuned encounters with the nonhuman.”

When Soleimani’s mother first arrived in the United States, she wasn’t able to practice nursing because of the language barrier. Instead, she rehabilitated birds and other animals. From a young age, Soleimani became her mother’s “apprentice” and, sometimes, “if there was a goose egg hatching, my mom would call and I would stay home from school,” says Soleimani. Together they would watch the bird peck through its shell and experience its first few moments of life. “In inheriting her therapeutic impulses, I now aim to work out a more philosophical relationship between government, the ways that humans create systems to take care of the self, and animal health care, the ways that, as human animals, we can better care for the nonhuman world,” adds Soleimani.

Her parents’ stories are also woven into nearly every corner of her home, which she bought in 2018 and shares with her partner, the literary scholar and writer Jonathan Schroeder, who helps with the clinic and, along with Soleimani, teaches at Brandeis University. Clustered in front of the bay window in the cream-colored living room are over a dozen plants — some almost tall enough to touch the 12-foot ceilings — a handful of which, like the cherimoya and tamarind, her mother grew from a seed and gave to Soleimani. There’s also a 30-year-old jasmine plant that blooms every spring, and from which her mother made flower garlands for Soleimani’s when she was a child.

Past the floor-to-ceiling library is a sun-soaked dining room that Soleimani calls the “war room” in honor of her father. “Growing up, my dad was like, ‘dinner is a place where you have important conversations, not a place for pretty “How’s the weather?” talk,’” says Soleimani. High above the dining table, which she salvaged from a secondhand store, hang artworks, including posters from the Art Workers’ Coalition, an activist group formed in 1969 that demanded systemic changes in the art world around inclusivity and representation, and a maroon Afghan war rug stitched with tanks and a mountain range, that was a gift from her parents when she graduated college.

Affixed to the front entrance of the home is a hand-painted sign on plywood with fantastical creatures mid-flight framing the words “Congress of the Birds.” This is what Soleimani calls her clinic and, seeing it, I imagine a big room filled with the competing chatter of bird songs. It’s also a riff on “The Conference of the Birds,” a 12th-century Persian poem by the Sufi poet Farid ud-Din Attar, in which the world’s birds search for a leader. In many ways, Soleimani has become a surrogate for the myth’s sovereign, who leads them on a path to enlightenment, until they finally discover it within themselves. “I don’t want to be the steward, but I am stewarding them,” she says, acknowledging the birds’ circumstances in a dangerous world, and the fact that she is using the wisdom of her family to give them back the gift of flight.