11 November 2022 The following is a preview of n+1’s new issue, MIDDLEMEN, out next month.

1. Isolation

I was born in a closed, totalitarian country. One would think that as long as a child didn’t know any other reality, they could be happy.

Here I am flipping through the pages of a children’s magazine for early readers: I study the pretty pictures and read the propaganda—stories about the USSR and its pioneers and heroes. Here I am at school: I’ve forgotten my red tie and am sent home to retrieve it. Here I am in the assembly hall after school, where the whole class has been forced to march and sing patriotic songs: there’s a Soviet holiday coming up and preparations are under way. I don’t want to march. I say that I have a headache, that I’m about to faint. I beg to be sent home.

My dad hates communism and makes a living drawing communist propaganda. My parents attend meetings after work, cheer at demonstrations, and give up the occasional Saturday to volunteer for the cause. I remember hundreds of details of everyday life in the Soviet Union, but how to convey what seems most important?

I’m on a high-speed train traveling from Brussels to Frankfurt. Two Europeans my age sit across from me. They smile when my gaze rests on them. Their faces are relaxed, their bodies loose and free. They have the look of people who have never known humiliation.

Life in a closed, totalitarian country means that you’ll inevitably come up against humiliation, which is itself a form of control and punishment. You can be talented, cheerful, brave—but if you contravene the system it will destroy you. You think about the fact that years before you were born, a group of politicians closed off the rest of the world to you: you can fantasize, speculate, assemble a picture in your mind based on stories told by strangers and on movies and photos, but you’ll never encounter the world that you’ve been cut off from. You’ll never taste it for yourself. The USSR collapsed in 1991, but I never lost the fear that I would again end up in a closed country where my life would be controlled by other people.

After my book was published in the US in 2017, I became a well-known writer. My work wasn’t published or shown in Russia because of censorship, so I started to exhibit and lecture in Europe, the US, and the UK. Even before the war in Ukraine and the subsequent sanctions regime imposed on Russian citizens it was hard to get a visa with a Russian passport. At the same time, every new bit of success—the publication of the book, a big gallery show—made returning home more dangerous. By 2019 it was becoming very difficult to balance life in Russia with my work abroad.

All my visas lapsed after the pandemic began in 2020, and it was impossible for me to acquire any new ones because I didn’t have access to foreign vaccines. So I spent two years in Russia without ever leaving. I roamed around my neighborhood in search of subjects for new work. I lived in Moscow, in a Khrushchyovka—a type of five-story building constructed in the 1960s across the country. The Khrushchyovkas in my neighborhood are faced with gray brick, and the impression one gets walking around is of moving through an endless gray light. Not far from my house is the enormous Izmailovo Hotel, opened in 1980. The concert hall enfolded by the complex is encircled by a bronze frieze that depicts similar-looking muscular athletes running, swimming, and jumping with parachutes. The space between them is taken up by waves, birds, and five-pointed stars. A bit farther down is the Izmailovo flea market, whose towers and turrets imitate the architecture of the Russian past and the baroque style of the 17th century. I looked out at this landscape and had the sense that time was bending backward—that the roofs of the Khrushchyovkas were being overgrown with moss and little towers and churches were pushing through.

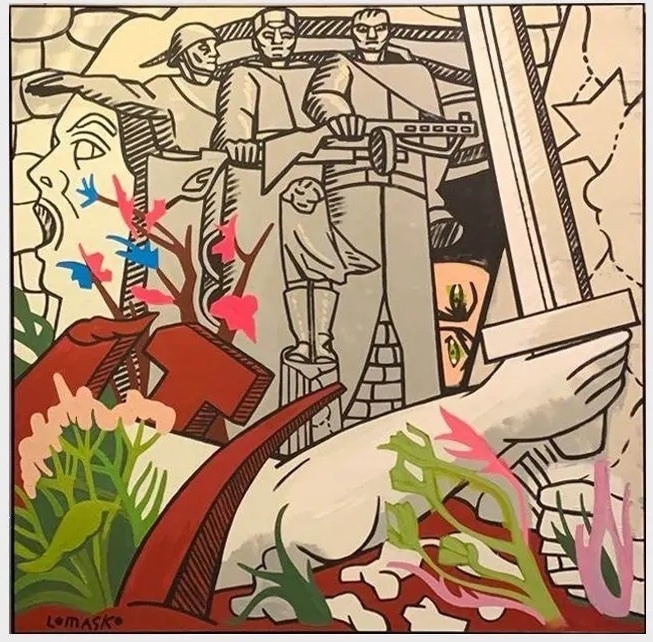

I was frightened by the number of posters I saw reminding everyone that we had been the victors in World War II. On the subway I occasionally ended up on the so-called Victory Train, which was decorated with photos of Soviet soldiers holding automatic rifles and anti-fascist posters. At first I tried to avoid the warning signs, but then I decided to describe and depict them. A number of times I went out of my way to visit the Patriot Park museum complex, where tanks are lined up in endless rows and the huge expanse is dotted with militaristic statues. At the park’s entrance is the Cathedral of the Russian Armed Forces, which resembles a horror movie castle. It was there that I understood that the Putin regime would pull us inevitably into a new war. It was there that I found the subjects for my new work: the gloomy forest, whose branches transform into automatic weapons and Soviet monuments that come alive to take revenge.

2. Escape

On February 24 I woke up at home in Moscow and read the news that Putin had begun the war in Ukraine. From that moment on all my thoughts were focused only on one thing: how to leave the country.

That same day, the dictatorship in Russia clarified itself: the center of Moscow was occupied by prisoner transport vehicles and the black cars of the National Guard raced through the streets with their sirens blaring. I heard announcements on the radio that any gatherings of people were banned “due to the tense Covid-19 situation.” There were constant news stories about arrests, and even on public transportation, in cafés, and in line you could hear fragments of conversations about people being searched and apprehended just for daring to say something against the war.

I overheard one conversation while waiting in line at the bank, where I spent a few hours hoping to withdraw euros from my account. A young woman was telling her elderly mother about women with children arrested at antiwar protests—she was also planning to attend the demonstration.

“Spring is here,” her mother said, trying to change the subject.

“War is here,” the daughter responded.

“We’re lucky that we managed to live for at least a little while without war,” the mother said.

I understood that if I stayed in Russia the police would soon break into my apartment. They would rifle through my drawings, read my writing, and destroy my archive. There is no justice in Russia: I could be imprisoned for three years, or maybe a decade. Putin could announce martial law at any time. He could close the borders. I began to have panic attacks. I had to change my shirt and my socks three times per day. My body was covered in a cold sweat. It would have been easier for me to run in the middle of a crowd, to throw stones and try to burn down everything in my way than to feel . . . how did I feel, exactly? The whole time I kept thinking of the footage from Kabul International Airport in 2021: the last airplane takes off and a crowd of people hoping to escape into the free and open world is left behind on the runway.

I managed to leave Russia on a short-term tourist visa. As I write this I’m on my seventh month in the European Union. The panic attacks haven’t gone away. The most recent one occurred when I read an article in the Washington Post titled “Zelensky calls on West to ban all Russian travelers.” “Whichever kind of Russian . . . make them go to Russia,” Zelensky said. When I read that I started feeling dizzy and wanted to throw up. It wasn’t enough that Putin had broken my life—now the so-called collective West would uphold the punishment? I decided that if I was ever able to come back to Russia, I would try to work with the younger generation—to teach them how to defend their freedom, and also never to trust the West.

When I finally calmed down a little I thought about what this collective West Russians have heard so much about actually represents. How is this community different from the one referred to as “Russians”? Some politicians demand that people be punished on the basis of their passports, some institutions boycott them based on backgrounds they can’t do anything about, some media organizations launch smear campaigns, and some countries close their borders and cancel visas. All this has happened, and at the same time the French Embassy in Moscow was able to give me a visa in a single day, a few hours before my flight, and later helped me transport my entire archive to Europe. The Vrije Universiteit Brussel and the Université Libre de Bruxelles helped me exhibit a new antiwar mural in the center of Brussels. The Akademie Schloss Solitude in Germany gave me a fellowship. My Western publishers, producers, and gallerists supported me over the past few months and became real friends, rather than merely colleagues. So it is up to me whether I want to focus on the people who seek to judge and punish me, or those who want to support and help.

Here’s what I’d say to President Zelensky: there’s room for an artist or a writer everywhere. This entire world is mine by birthright.

3. Exile

Why didn't I bring my favorite calligraphy pens with me? Why didn’t I bring my favorite drawing pens? That tiny pen box wouldn’t have taken much room in my suitcase. I’m standing in the middle of Schleiper, a huge art supply store in Brussels. It’s my second day in Belgium and I’ve come to buy drawing materials.

When tragedy strikes, rational thought is abandoned. I don’t think about the elderly parents I’ve left behind; about the friends in danger in Russia; about my Moscow apartment, which I’d transformed over the years into a cozy workshop. I think about my pen box.

I don’t remember when I first held a calligraphy pen and began to draw in ink. I must have been 8 years old. It was my father who gave me the pen box. Before the Soviet Union fell he worked as a graphic designer in the Metallist plant in Serpukhov. He used these calligraphy pens to sketch posters that were produced for communist holidays. When the Soviet Union broke apart and all the artists were fired, he brought home a few boxes he’d been given at the plant. They were supposed to last him—and me—the rest of our lives. And here I am in this enormous store, and I can’t find the right kind of pens. Everything I try produces totally different lines.

I began adding text to my graphic reportage in 2007, and at the time I couldn’t imagine how far that would take me. At first I simply drew people in public places, listening in on their conversations and transcribing them as they happened. Eventually I began to understand that there are hundreds and hundreds of important stories happening all at once—happening right now—and if I didn’t try to capture them, no one would.

In 2009 I went to draw the trial of the curators of an art exhibition called Forbidden Art, which displayed work that had been banned and censored at other exhibits. The case had been cooked up by Russian Orthodox activists. In the course of drawing the trial I received the first threats I’d ever gotten—the activists promised to come to my home and lie in wait for me, to “draw all over me” so hard that I wouldn’t be able to draw my own work. There were many days in the courtroom when there was no one on the defense side other than me. Returning home with new drawings in my backpack, I felt afraid.

Over the next decade and beyond, I drew the residents of Russia’s provinces, the pupils of its juvenile prisons, the teachers and students of its rural schools, its sex workers, its lesbian couples, its activists, its citizens who participated in opposition protests and protest camps. I also drew numerous political trials, each of which ended with the punishment of the opponents of Putin’s regime. I tried to give these opponents a voice, to make them visible. Now I carry all these people and their stories in my heart. And while the Western media expects Russian dissidents to publicly condemn the entire Russian people, I have no plans to betray them.

A few days ago the mobilization began in Russia. The first order of business is to catch men who live in the provinces, especially in regions with sizable ethnic minority populations. Women, old men, and children are thus left all alone. People who could barely get by as it is now don’t know what to do. And somewhere far away, in a world that’s unfathomable and inaccessible to these people, European politicians discuss how to punish them so comprehensively that they finally depose the Putin regime. To oppose such a dictatorship, a person has to be ready for death. This is the kind of decision that every person has to make for themselves.

4. Shame

The depths of night. I’m sitting at a desk that’s not my own and making sketches for antiwar murals. Suddenly my friend A. starts to scream. She’s seven months pregnant. We’re in a little mansard apartment that belongs to the friends of our producer—we’ve been settled here. We escaped from Moscow together: Moscow–Bishkek–Istanbul–Paris–Brussels.

A. really didn’t want to leave—she loves Russia, Moscow, and the father of her child. But he has participated in every single antiwar and anti-government action and has been arrested a number of times. The next time it happens he’ll face criminal charges. A. spent days waiting for the doorbell to ring, or for the FSB to simply break down her door. After that she went in for a checkup and was told by her doctor that her baby’s heartbeat was inaudible. A. was sure she was about to lose consciousness. In the end the doctor determined that her child was still alive. After that, A. decided to escape with me. She didn’t have any money. Our debit cards no longer worked on the other side of the border because of the sanctions, and A. wasn’t able to withdraw any euros from her online bank in Russia because the ATMs were out of money. Her insurance didn’t cover her in Europe, so she wouldn’t be able to see a doctor easily.

And now she’s screaming as if someone were murdering her, and I—the person who persuaded her to run—am frantically searching the internet, trying to figure out what can help pregnant people when their legs cramp. I apply some wet rags and look for the phone number of the local ambulance service. We don’t end up calling, though—what if the service isn’t free? We have nothing with which to pay them.

Every morning in Brussels, A. would head off to a studio on the other side of town, where she was editing her new documentary. I spent entire days sitting in the mansard room drawing sketches for a mural and comics and caricatures about the war in Ukraine and the dictatorship in Russia. A. would return in the evening and I’d make pasta with ground beef. A. always knew the latest news from the war, and of course I did, too. As soon as she entered the room we would launch into frantic discussions of what was happening that day in Russia and Ukraine. It seemed that the ruins of bombed houses and the bodies of the dead were present in our midst, invisible but inescapable.

What did we feel? Anguish. Grief. Shame that the criminal Putin regime was committing all these new crimes in the name of Russian citizens. Did we feel collective guilt? I didn’t. For over a decade I’d done as much as a political artist could. A. didn’t feel guilty, either. She was born in the provinces and had worked hard to get to Moscow. She financed her own social and political filmmaking, worked with migrants from Central Asia, and participated in every possible protest action. Even so, as we sat at someone else’s table eating our pasta, it seemed to us that we were in the presence of shadows—the shadows of people fleeing the bombing in Ukraine.

When, two months later, it was time for A. to give birth, she set off for a local hospital that served the homeless, migrants, and other vulnerable groups, hoping to get free medical care there. After spending the entire day in line, she couldn’t make any headway. A few days later her tourist visa ran out and she became illegal. In the end she did end up giving birth at that hospital—and subsequently received an enormous bill. At the time of this writing she’s planning to return to Moscow, where her home was the target of a police raid—they were looking for her partner.

5. Humanity

When I hear the calls to “cancel” Russian culture, I think: Go ahead and kill me, too. I have no other path, no other identity besides being an artist. I can’t change my blood, and you’ll never grant me any citizenship. I’ve become increasingly certain that I’ve spent my entire life drawing a single work of art—one that takes as its subject freedom of choice and the uniqueness of every individual. If I’d been born in the US, or China, or Iran, or anywhere else, I’d be doing the same thing—the only thing that would change would be the names of people and the backdrops.

What is a nationality? If an activist who comes out against the war and the police officer with Z on his back who beats him up are the same entity, then that being must also include in its ranks all the Western politicians and businesspeople who collaborated with the Putin regime for decades. It includes the Western intelligentsia now practicing its selective so-called humanism.

“Everything is so fucked up right now,” a German friend wrote to me. “All kinds of values we relied on no longer seem to apply.” This friend has always focused on political art and fighting censorship—throughout her career she has cooperated with artists in the line of fire. These days when I read the Russian press and the Western press, I sense that they’re united in one key respect—everyone seems to think that in a time of war, real humanism is too great a luxury.

When we’re involved in larger historical processes, every person’s choices fall somewhere on a spectrum that includes crime, indifference, and heroism. It is obvious that a person who calls for murder and destruction in Ukraine and a person who helps refugees in Russia at great personal risk represent two absolutely different universes. Behind these choices is someone’s entire life: the millions of little choices made up to that moment.

Geopolitical games that operate on the basis of clear distinctions between good nationalities and bad ones cannot lead anywhere healthy. But the idea of a single humanity composed of unique individuals is a pledge toward collective progress. I worry that there are many difficult challenges ahead, and only once we pass through them will we recognize that we are one. Still, I’m not envious of those whose position is more stable than mine. The changes we face are so enormous that there will only be one way to approach the future: with empty hands.