12 May 2023 Victoria Lomasko: social justice reporting.

Victoria Lomasko (b.1978) was called one of the best masters of graphic reportage in Russia a decade ago. Today her exhibitions are held in Europe and America, her books have been translated into major European languages and published in various countries. However, in Russia, this socially engaged graphic artist has not been exhibited for many years, her main books have not yet been published, and her paintings have not been seen at all.

Victoria Lomasko was born in Serpukhov into an artist's family, but don't think that the bohemian atmosphere at home and her parents' artistic connections predetermined her career. Her father, Valentin Lomasko, worked all his life as a factory graphic designer and was, in fact, self-taught - he graduated from ZNUI (Part-time National University of Arts) and studied painting by correspondence. Agitprop for the plant, Serpukhov landscapes for himself and all for his daughter - he dreamed that she became a professional artist and that her creative destiny took a more successful course. The daughter lived up to expectations: an art school and a pedagogical college (a diploma in drawing teacher) in Serpukhov, a Polygraphic Institute (a diploma in book graphics) in Moscow. Secondary art and pedagogical education will be useful to her later in volunteer work: in August 2010, at the invitation of human rights activists from the Center for the Promotion of Criminal Justice Reform, Lomasko came to the Mozhaisk children's colony to give one drawing lesson - and at the end of the master class she could not tell the teenagers that there would be no next lesson. For five years in a row, she went to teenage correctional colonies for boys and girls: she developed lesson plans, prepared visual materials, books and printouts, talked about art - everything was taught in a pedagogical college. She drew little herself - the main goal was not so much a graphic report on juvenile prisoners, but the experience of social therapy and rehabilitation, it is no coincidence that Lomasko sought to exhibit drawings and painted ceramics of students outside the colonies, in the wild. Once they were shown along with the works of a ZNUA graduate of the early 1960s, who was taking his epistolary university course, serving time in the camp (perhaps he was a correspondence classmate of Lomasko's father - ZNUU students usually did not know each other). After the archive of the Drawing Lesson project was exhibited at the Reina Sofia Art Center in Madrid in 2014, the artist donated the work of members of her prison art circles to the Spanish Museum for safekeeping.

After her graduation from Polygraph, Lomasko stayed in Moscow, where she earned money as a commercial illustrator, tried painting, and joined the leftist "Radek" group. In 2008, Lomasko started her first systematic experiments in graphic reportage: she wrote the "Notebook" column on Artinfo.ru and became an art chronicler, drawing "pictures of exhibitions". In February 2009, at the entrance to Gorky Park, an artists' meeting was held against Luzhkov's plans to demolish the Central House of Artists. The commentaries on the vernissage drawings were composed by artist friends. Even though Lomasko herself has been writing since her early childhood and even earned her first royalty at the age of six by sending her poems to some pioneer newspaper, at first she limited herself to small forms of literature, that is, character lines in comic "bubbles". The search for a co-author-literator brought her together with Anton Nikolaev, the founder of the group "Bombily" and a journalist at the same time: she would learn reporting techniques from him - making contact with people, taking interviews, he would begin to draw under her influence. The "bombshells" who proclaimed themselves the new Itinerants practiced trips to the outback to meet with the "country folk", Lomasko accompanied them as a "court painter" - these expeditions resulted in Lomasko and Nikolaev making several absurdist comics together and the first book, The Province. Lomasko and Nikolaev's second book together made them famous all over the world, though they quarrelled over copyrights.

In May 2009, the Moscow Tagansky Court resumed the trial of Yuri Samodurov and Andrei Erofeev, curators of the Forbidden Art 2006 exhibition - artist-activists had turned this political trial into a festival of protest actionism, and the first among them were the "bombers" with the "Fascist Beating Themis" action. Lomasko came to paint the "bombshells" - and went to court sessions as if she were at work, for a year and a half, until the verdict was appealed. The book Forbidden Art (with drawings by Lomasko and texts by Nikolaev and Lomasko) was published in St. Petersburg in 2011, some time later it was translated into German and French, but at the height of the trial Lomasko's drawings began to be published in Russia and abroad - in the media, writing about censorship and repression, and in academic publications that looked into various aspects of the conservative turn in Russia. A conflict later arose between the co-authors, Nikolaev demanding copyright over the drawings - all ended in a reconciliation, but they no longer worked together. The reasons for the disagreement were more serious than the dispute about the copyright: Lomasko began to realize that the satirical approach, despite the fact that the subject begs for such an interpretation, was not close to her. Although Orthodox activists, who became protagonists of absurdity at the trial and, accordingly, the protagonists of the graphic reportage, threatened the artist with reprisals, she regretted that the witnesses for the prosecution appeared somewhat caricatured.

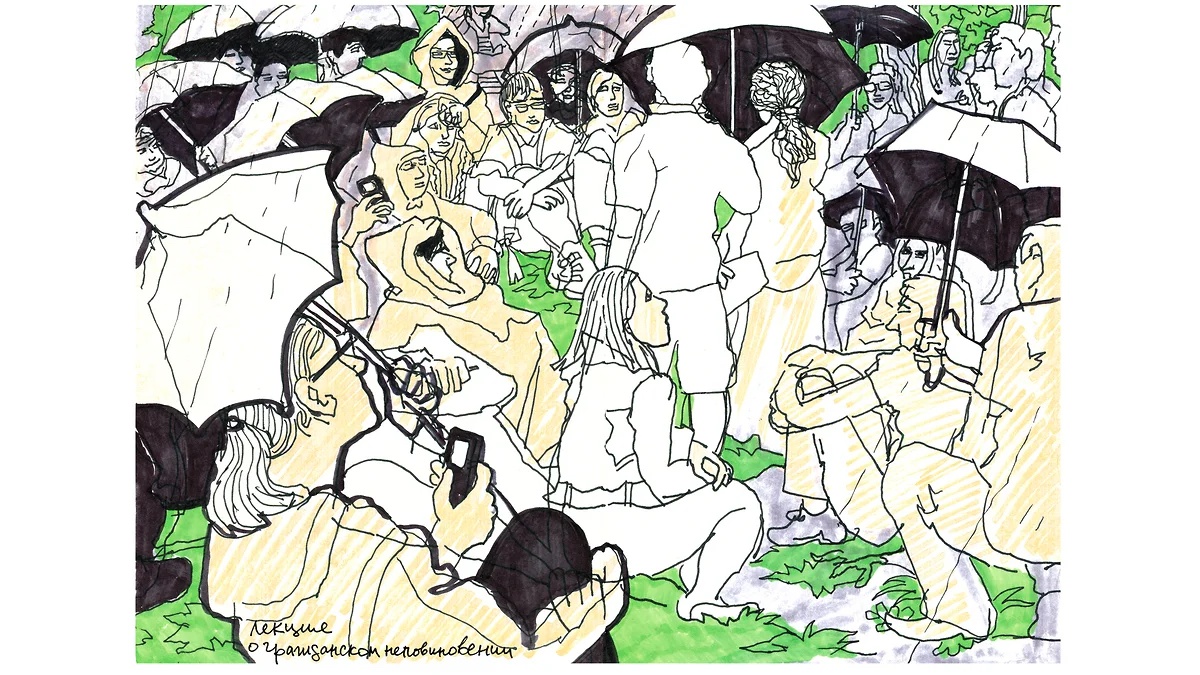

During her work on Forbidden Art, Lomasko developed a reputation as a political activist - journalists loved the image of the sketchbook artist who sketches her momentary sketches right in the street, among protesters and police, from the heart of events, and sets up exhibitions in subways or protesters' camps. She has painted constantly in courts and at protest rallies, worked with human rights activists, civic activists and environmentalists, and reported on socially vulnerable groups - teenagers in penal colonies, sex workers, migrant workers, LGBT people, HIV-positive people. She was not only interested in the 'occupation' camps on the Boulevard Ring - with their trendy bohemian crowd - but also in the Khimki camp of long-distance truckers who opposed the Platon system. Many people thought that the all-Russian protest of truckers might become a revival of the trade union movement; Lomasko was the initiator of two group exhibitions, "Feminist Pencil" (made together with Nadezhda Plungian) and "Drawing the Court" (made together with Zlata Poniroffskaya), which could become a kind of union of like-minded people. But even before Forbidden Art, she had begun to work on the portraits of "ordinary people" - from the electric train, the queue at the outpatient clinic, the beer house, the fleabag, the flats in a block of flats, alone, forgotten and unneeded. The two Russias, politically active and excluded from political and not only political life, "angry" and "invisible", will later meet in the book Other Russias.

Victoria Lomasko, from Other Russias, 2017.

Victoria Lomasko: "My job is to help talk"

Both in Black Portraits, where the hero's entire life fits into one drawing and one line, and in the large graphic reports it is clear that Lomasko is a master of polyphony. In the sense that the story is always composed of many voices, and in the sense that each character is polyphonic in its own right, whether it is an Orthodox activist who was once a militant atheist, or a Dagestani woman who becomes the battleground of traditionalism and social modernization. As the polyphonic picture of Russian society in Lomasko's graphic art became more complex, so did the technique of drawing: from black-and-white they gradually turned into colour; ascetic ink was replaced by isografs, felt-tip pens, oil crayons and watercolours; only the strong stained-glass outline which kept the dynamic compositions from disintegrating remained a constant. The very structure of graphic reportage changed: "comic" drawing in symbiosis with brief text ceased to dominate, there was more space for literature, documental testimony of the artist who wrote about what he saw, directly and clearly, as the stained glass outline.

Nevertheless, it was not only Lomasko's art that was becoming difficult, but also her life in Russia: works were withdrawn from exhibitions, exhibitions were cancelled, reports risked being published only by rare independent media, books were not published at all - the Russian-written Other Russia (2017) and The Last Soviet Artist (2022) were published in numerous translations abroad. It was noticeable that her vigorous drawing was cramped in a book: at exhibitions in the US and Europe, she began to make murals, monumental graphics, first directly on walls, as on blank paper, then on large-format wooden panels. In the murals, Lomasko shifts from a documentary language to a symbolic one: motifs of reportage graphics blossom into complex allegories of contemporary Russian life - if the exhibition space allows, the murals encircle the viewer on all sides, so that he gets inside a big fantasy story, where the post-Soviet present is inextricably linked with the Soviet past. In short, those critics who used to compare Lomasko to Joe Sacco and Marjan Satrapi might now think of Mexican muralists.

It is not only the exhibition geography that has expanded - The Last Soviet Artist contains cycles made in the second half of the 2010s in the Caucasus and Central Asia, in Dagestan, Ingushetia, Armenia, Georgia and Kyrgyzstan: instead of Orientalist exotica, we see the same poverty, lawlessness, xenophobia, homophobia, religious intolerance, a hybrid society of patriarchy and modernity, where it is most difficult for women. The book closes with reports from Minsk and Moscow, from the anti-Lukashenko protests in the autumn of 2020 and the pro-Navalny rallies in the winter of 2021. In his long-distance expeditions, The Last Soviet Artist reveals the essential unity of the post-Soviet space - the space of shared destiny and misfortune. In addition, the wanderings within the borders of the former Soviet Union allowed the artist, so sensitive to the spoken word, to remain within the confines of the Russian language. In the spring of 2022, Viktoria Lomasko left Russia for the West, but managed to cope with the language barrier: making a graphic series about the discussions in documenta 15, where her "courtroom" drawings from the Forbidden Art and Pussy Riot trials echoed, she became quite comfortable in the environment of international English.

Masterpiece: The Last Soviet Artist. Exhibition at the Santa Giulia Museum in Brescia. November 2022 - January 2023

The book The Last Soviet Artist, already published in Spanish, Catalan, French and German translations, gave its name to the exhibition, where graphics and monumental paintings are interwoven into a single installation, a biography of the author against the background of dictatorship and exile. The original drawings for all three books, the fantasy series Frozen Poetry, painted during the pandemic, the anti-war mural The Change of Seasons, the cycle of monumental panels Five Steps, made during a year of exile, all finally come together in one artistic world. The leitmotif of Lomasko's monumental painting is struggle - not a struggle of good against evil, black against white, right against left, progressive against backward, but struggle as such, as movement, as the opposite of stagnation, as the meaning and purpose of human life and history. The images refer back to the Soviet monumental art - not only to its early and lofty examples, though Lomasko often speaks of her love for Alexander Deineka, but to the commonplace and routine ones, the kind you could meet in any district centre of the USSR and on which her father worked all her life, hating the regime he served as much as his daughter - the one she tried to oppose. The fight for a brighter future was by default the main plot of these ideological set pieces - it would seem that the play has long been removed from the repertoire, but as long as the actors - Lomasko's heroes and herself as part of the troupe - are alive, the memory of its humanistic pathos and human content lives on.