23 May 2023 In 1634, during the Dutch Golden Age, an unprecedented financial phenomenon began in the form of skyrocketing prices for rare and fashionable tulip bulbs. By 1637, the speculative bubble collapsed, and while the plummeting price of tulips may have bankrupted a few investors, it didn’t take a steep toll on the overall economy, unlike the U.S. housing bubble that spurred a global crisis and led to severe recession in 2008.

“Tulip mania” is a term still used today to describe when the prices of assets—such as mortgages or technology—rise exponentially from their intrinsic or general market values and present a threat to economic stability. For London-based artist Gordon Cheung, Dutch still-life paintings provide a lens through which to explore ties between historical socio-economic systems, modern capitalism, and China’s new power on the global stage. “In part, they are about the rise and fall of civilisations, as well as the romantic language of still-life painting: futile materialism and fragile mortality reflected by the transient beauty of flowers,” he says.

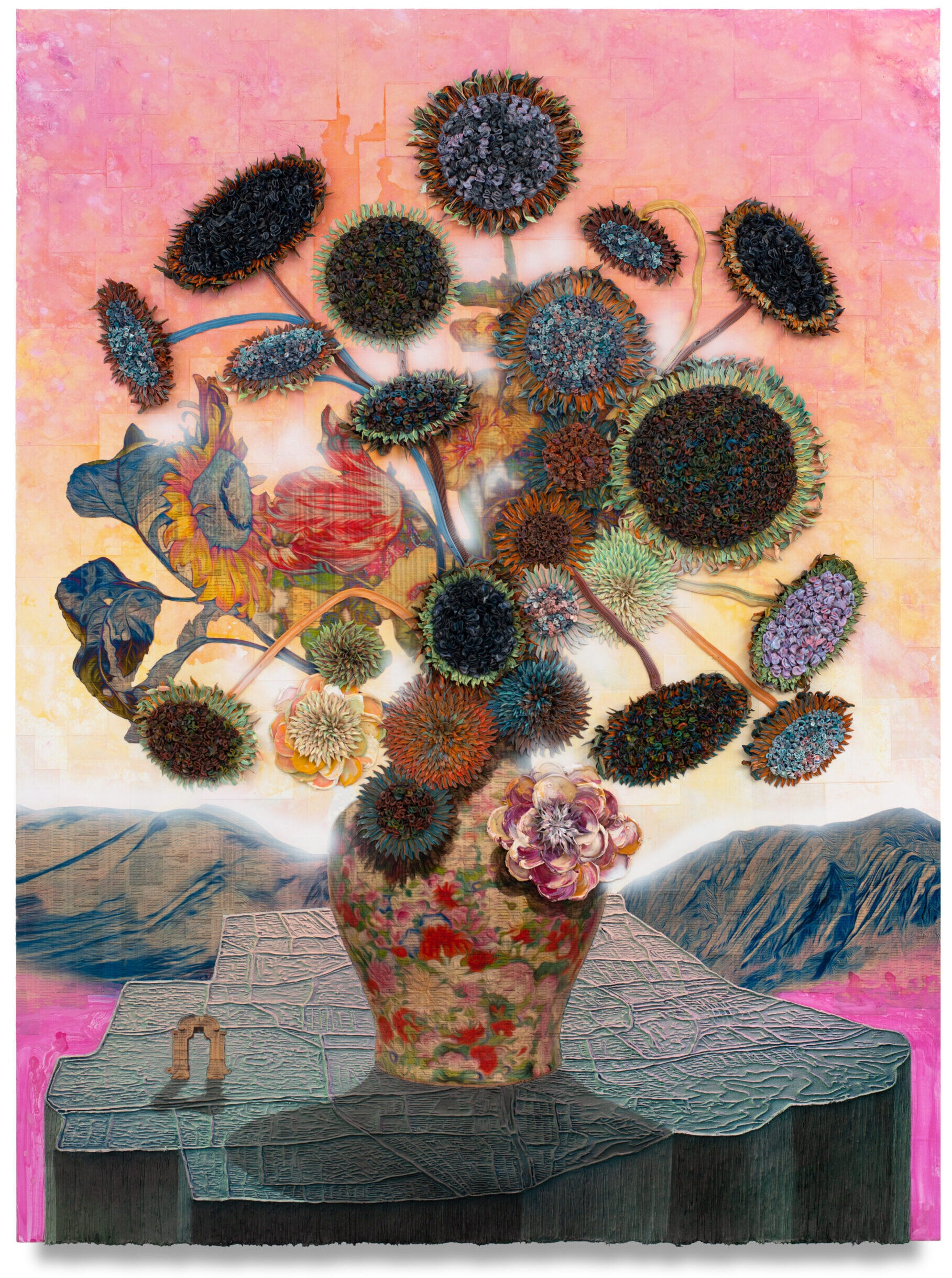

Like much 16th and 17th-century Dutch painting, the artist’s still-lifes brim with symbolism and references to historical events. The linen surface is collaged with pages from the Financial Times, literally grounding the work in data and news about the global markets. The painting above, for example, references the Old Summer Palace of Beijing, also known as Yuanmingyuan, which translates to “Gardens of Summer Brightness.”

Gordon Cheung, Gardens of Perfect Brightness, 2022, Financial Times newspaper, archival inkjet, acrylic, and sand on linen, 200 x 150 x 3 cm. © Gordon Cheung

The residence of Qianlong Emperor and his successors, the Summer Palace was home to celebrated gardens and an enormous collection of historic treasures and antiques dating back thousands of years. French and British troops captured the palace in October 1860 during the Second Opium War, which led to mass vandalism, looting, and eventually, total destruction.

In “Gardens of Summer Brightness,” the two holy mountains of Sinai and Song flank the vase in the background, suggesting a collision that may have led to the fractured pillar. A map of the park punctuated by an architectural ruin tops the pedestal, and the mille-fleurs or “thousand flowers” style, a popular motif in the Qianlong period, decorates the vase. The vessel also contains botanicals by the emperor’s court painter Giuseppe Castiglione and sunflowers to symbolize the face of the sun as a deity and energy source.

Combining inkjet printing methods, acrylic paint, and sand to create a variety of textures and three-dimensional features, Cheung’s flowers appear to delicately float across ethereal surfaces. He assembles each bloom by applying thick paint onto plastic that can be peeled off when dry and collaged onto the canvas. He is interested in what he calls the “Ozymandian eventuality” of grandeur and power to physically and metaphorically crumble over time, using sand to represent impermanence and the constantly shifting nature of the human condition.

Cheung’s solo exhibition The Garden of Perfect Brightness opens at The Atkinson in Southport, England, on June 3. You can find more on his website, and follow Instagram for updates.