30 November 2023 Recently acquired by the V&A in London, the photographer's Ghostwriter series is inspired by her parents' life stories and the events that mark the socio-political reality of the Middle East.

Known for her projects at the intersection of sculpture, performance, video and photography, Iranian-American artist, activist and academic Sheida Soleimani (1990, Indianapolis) turns to art to stimulate critical thinking about the events that punctuate the socio-political reality of the Middle East, bringing to the surface the insidious power dynamics that determine its relationship with the West.

"This series represents my first attempt to narrate the exodus my parents went through while fleeing Iran as political refugees", explains Sheida Soleimani (1990, Indianapolis), Iranian-American artist, activist and academic, in the video introducing Ghostwriter, her third solo exhibition at Edel Assanti, which ended last May. Dedicated to the project of the same name, the exhibition developed from a map drawn by her father to chart what, for him and his wife, constituted the "way out" of the totalitarian regime established in Iran at the end of the revolution in the early 1980s.

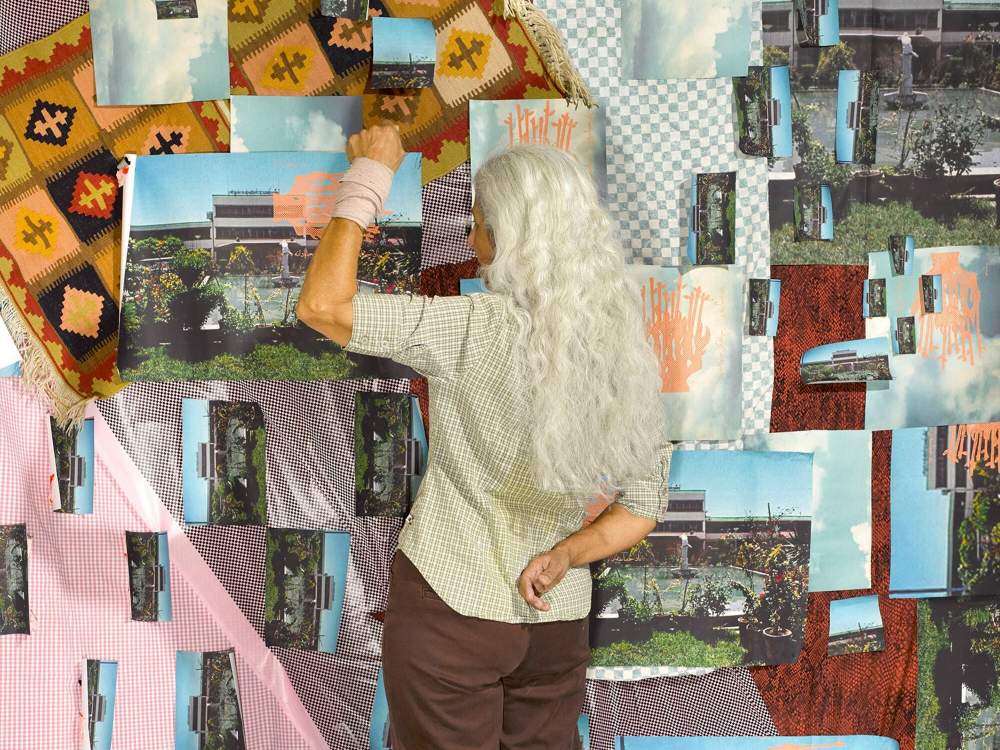

First shown at Providence College Galleries in the spring of 2022, and subsequently exhibited with new additions at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (Banner Project) and the Denny Gallery in New York (Birds of Passage), this body of work sees Soleimani documenting her parents within hypnotic settings, made from a wide variety of materials: from simple scraps of coloured paper, photographs of settings echoing his family's past and garish wax tablecloths, to birds, Arabic drawings and characters, fruit, branches, vintage suitcases and Persian carpets.

In the photographic series, recently acquired by the Victoria & Albert Museum, Soleimani focuses her lens on her Bâbâ and Mâmân (activists and health professionals) to 'rehabilitate' their memory in relation to the trauma of exile. In the different iterations of the project, the map on which the artist's dense photographic tableaux stand out has changed, transporting the audience from her mother's childhood garden outside Iran, back, with her latest installation, to the hospital in Shiraz where her parents met in 1975. Thus bringing them back, albeit only metaphorically, home.

We interviewed the author to find out more about the path that gave rise to this series.

Sheida Soleimani, Dissident (Mâmân), 2023.

From Shirin Neshat to Shadi Ghadirian, Shirin Aliabadi and Arghavan Khosravi, Iran's cultural landscape is studded with revolutionary female artists. When did you realise that this would be your path?

In 2010, during my second year of university, I got a scholarship to visit the remains of my mother's house in Iran and the place where she had buried 8 children under her favourite childhood tree. Initially, I was making still lives of dead birds, images for which the Iranian government could not consider me a threat. However, I wanted my work to be about my parents' stories. I was about to get my Iranian passport when my family in Iran warned me that it was not a good time to go there because of the political situation. So did the university who, worried, told me to choose a different country to go to. I wondered if I would ever be able to visit Iran, or if I should limit myself to creating 'non-political' works to preserve the hope of succeeding. At that moment, I realised that focusing on that was selfish: having the ability to speak freely in the US without being censored, I had to use my works to address political issues related to Iran. From 2011 onwards, my production focused on the history and socio-political climate of my home country and my parents' stories.

If your art could fulfil only one function, what would it be?

Convincing people to re-evaluate their perceptions of the 'other', of events of socio-political significance and of themselves.

What steps precede the realisation of your works?

I always start with an event, be it a political fact, an oral history or a memory, and sometimes all three. I then proceed to research it through the testimony of survivors, media images and archives of various kinds, so as to develop the thematic interests at the heart of my paintings. After that, I begin to sketch the idea of the 'still life' I want to realise, considering props, symbols, colours, and images. The physical construction of each set comes after weeks of research: I often shoot the same scenes several times before I am satisfied with the final result.

What prompted you to shift your focus to "the inside" in Ghostwriter?

I had never made such an intimate work before and my biggest fear was that it would be overly sentimental. I then realised that as long as I approach sentimentality in an ethical and collaborative way, the series would still be a success. I have dreamed of taking this step my whole life, I just never had the right language to do it, or the maturity. Now I feel ready.

Already a pivotal motif in traditional Persian art, birds and pheasants feature prominently in this series. What is their significance?

In giving a biographical and political essence to my parents (migrants and refugees) and the migratory birds, I am not only trying to show how they are continually damaged as life becomes 'non-life' on a planetary and national scale. Rather, in contrast to the humanitarian pornography of pain, Ghostwriter treats these living beings as subjects, agents and creators of dignity-oriented worlds, describing their stories distinctly and in tandem with each other to generate new ways of seeing, imagining and being in the future.

(Translated from Italian)