Extraordinary journeys. Victoria Lomasko in the post-Soviet republics.

In exibart's Extraordinary Journeys column, artists recount out-of-the-ordinary experiences that led them to reflect in new ways on the world and themselves. A mapping to see places, research, inspirations with new eyes.

Victoria Lomasko, The Last Soviet Artist

I don't know how magical the word “travel” sounds in Italian; in Russian it is “путешествие,” combining “path” and “follow the way”; the word is so devoid of temporality that, when you pronounce it, a space begins to unroll like a scroll. I discover a difference between “travel” and “trip” (in Russian as in English there are two different words, but it seems to me that in Italian there is only one). In my view, “trip” implies different actions in the physical world, no matter whether for work or leisure, while “travel” implies the transformation of a person who has embarked on a journey.

For example, for my graphic book The Last Soviet Artist, which was recently published in Italy, I made seven trips and the chapter titles are these: A Trip to Bishkek, A Trip to Yerevan, A Trip to Tbilisi, A Trip to Dagestan, A Trip to Ingushetia, A Trip to Osh, A Trip to Minsk. The goal was to collect materials; my work was about the intersections of sociology and journalism. From these trips I remember several adventures: for example, when in Dagestans I was almost kidnapped to become a second wife, or when I illegally crossed the border of Belarus during the pandemic, hiding in a large travel bag.

Victoria Lomasko, The Last Soviet Artist

The single “trip,” taken together with the other “trips,” formed a magical “travel” not only through the so-called “post-Soviet space,” but also through time. It inspired my transformation from graphic journalistad artist and writer.

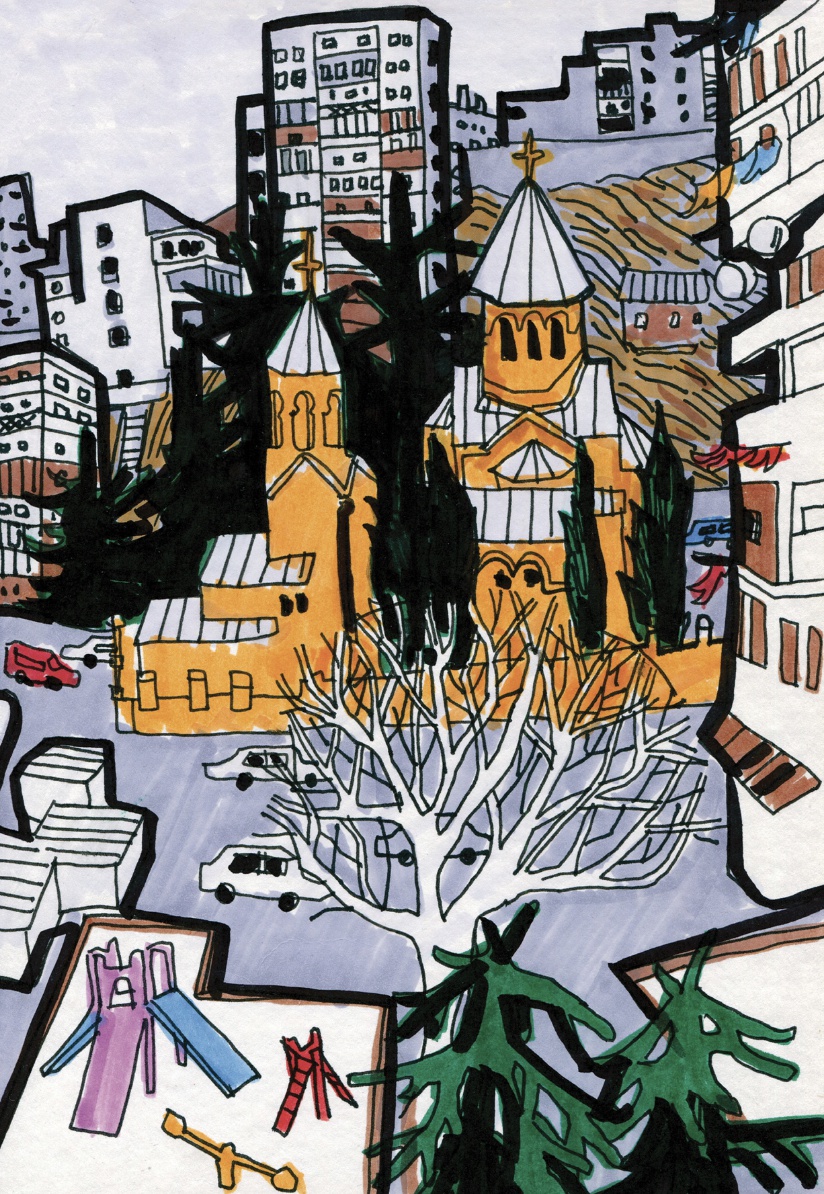

Although I was born and raised in the USSR, I never travelled through the Soviet republics as a child. I envied the boy Dima, a character from the children's magazine FunnyPictures, who boarded a magic plane and visited all the republics in one day. Instead, my travels through these places began only when I was over 30 years old. I did not want to follow the path of the Russian Orientalist artists, I did not want to be someone who came from Moscow, the centre of the former Soviet empire, to collect “exotic” material. I only visited places where I was invited by local communities, mostly feminist groups, to do workshops with social purposes, where participants shared their thoughts and concerns. Many became my guides, and I became their “pencil” to document local issues. In Yerevan, we wandered through a historic neighborhood that was about to be demolished; in Tbilisi, we visited a building occupied by homeless people; in Dagestan, we embarked on a dangerous expedition to some high-altitude villages where female genital mutilation is still practiced.

Victoria Lomasko, The Last Soviet Artist

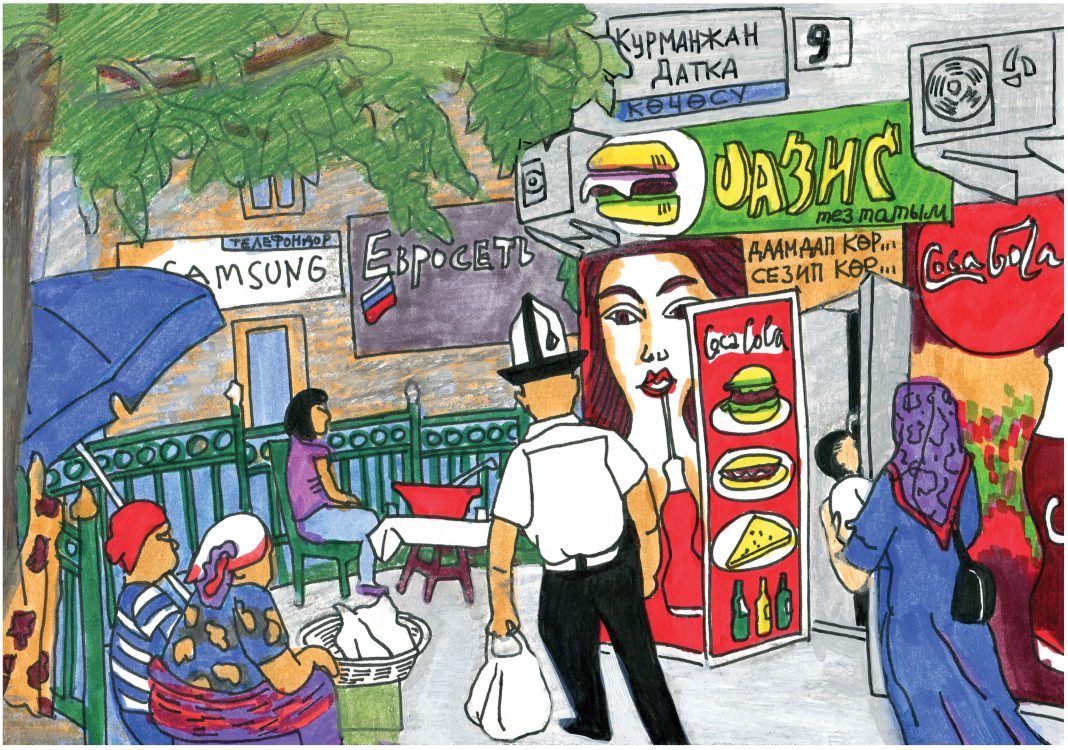

When I was alone, I used to wander around the city, drawing people and landscapes. One can understand a lot about a foreign country just by carefully observing the flow of daily life. For example, women in hijabs sitting under Coca-Cola tents, men in kalpak national headdresses and girls in miniskirts walking down the streets; the writing on billboards begins in Kyrgyz, continues in Russian and ends in English... This is Central Asia, a place of mixing many cultures and political influences. And this is Georgia, a country where the influence of the Orthodox Church is incredibly present. In all the cities I found relics of the Soviet empire -- a communist monument with a deteriorated nose, a decayed five-pointed star or fragments of pompous mosaics.

Victoria Lomasko, The Last Soviet Artist

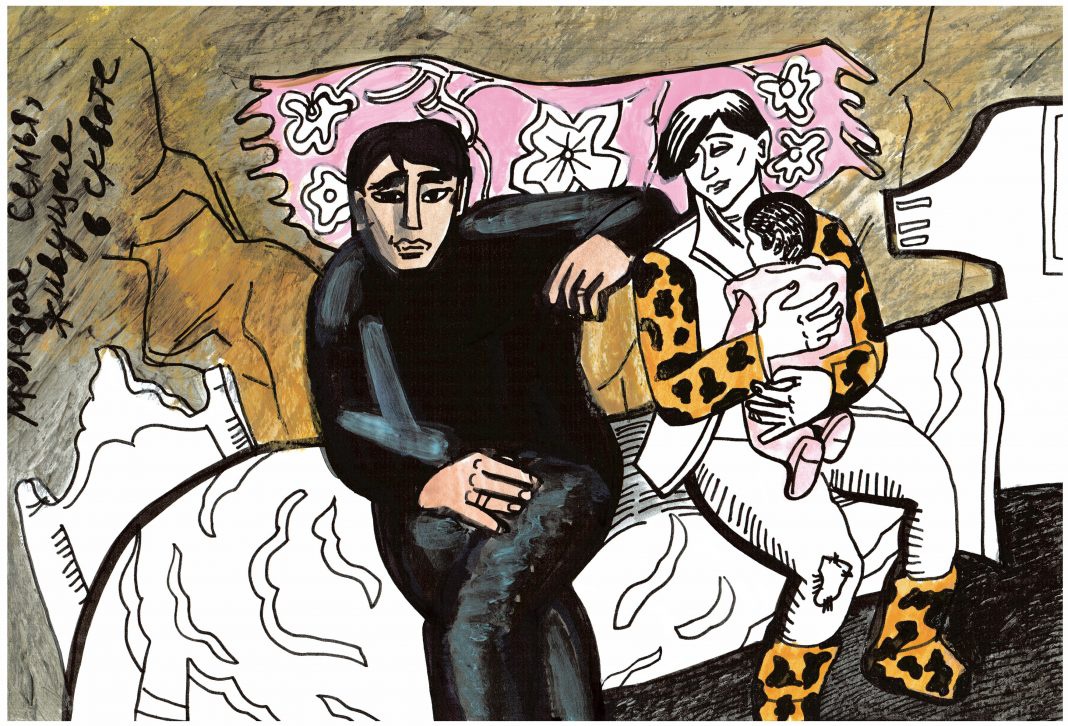

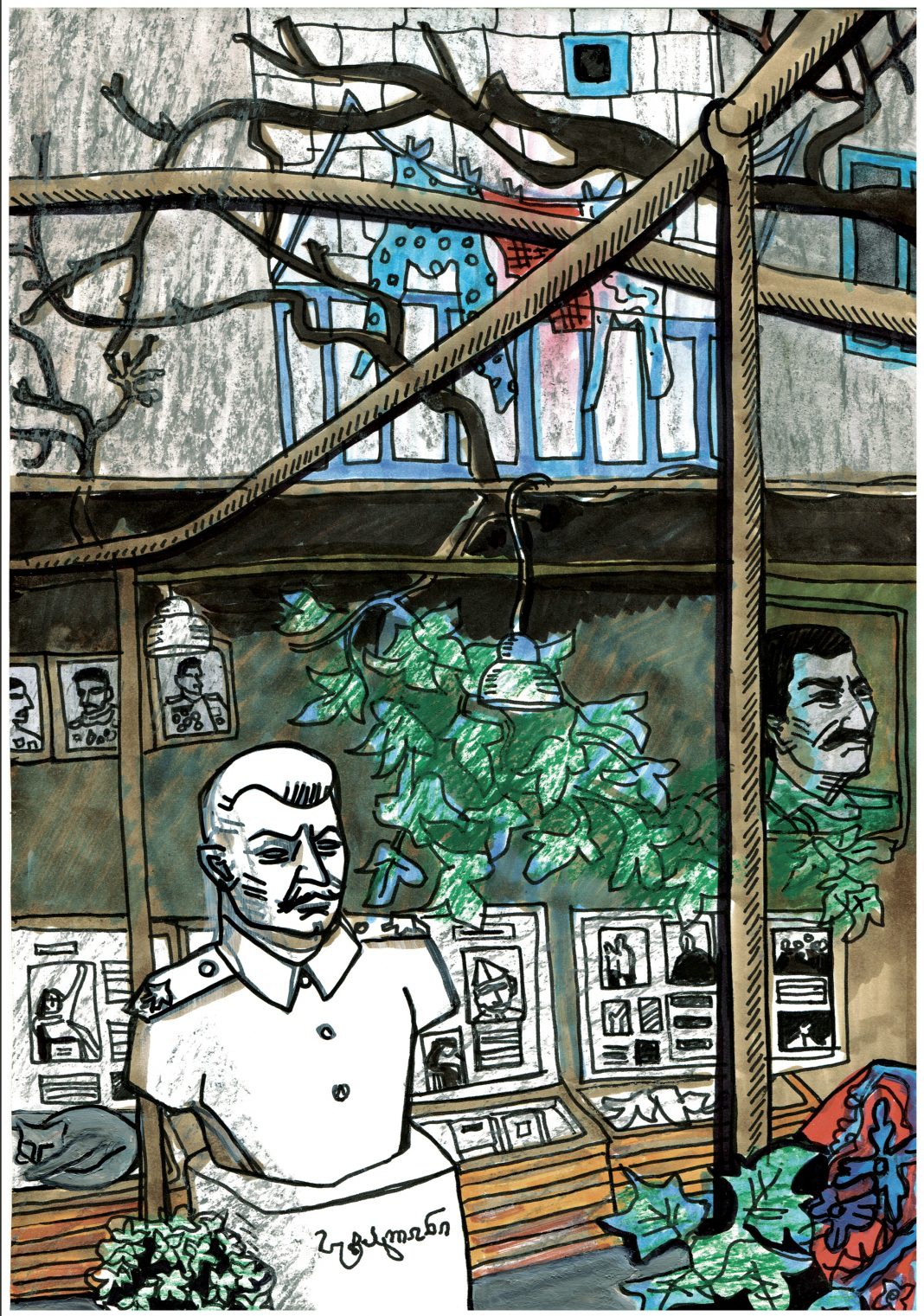

In contrast to the monolithic representation from Soviet books, the knowledge gained through the multitude of stories people have told me composes a kind of colorful carpet. An old Dagestani man raged remembering Stalin's deportation. Another old man created a Josef Stalin museum in his private garden in Tbilisi. A family showed me the medieval Ingusce towers. Taxi drivers and security guards told about when they worked as engineers in their “former life” and how happy they were. People remembered not only the period of building a utopian state, but also the period of their youth. The Soviet matrix is neither a good thing nor a bad thing; it is just a part of our lives.

Victoria Lomasko, The Last Soviet Artist

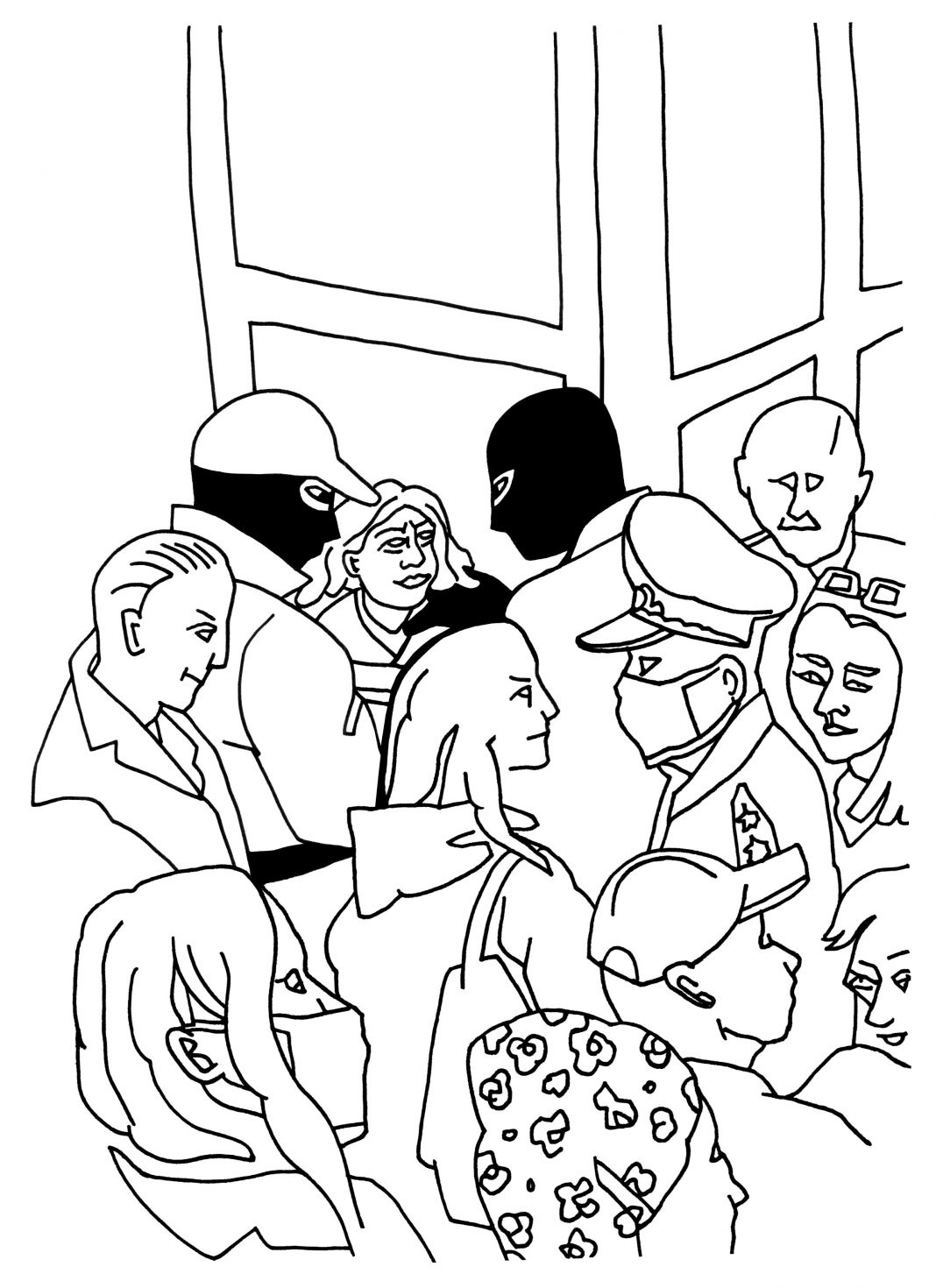

If I had to describe one particular trip, I would choose a trip to Minsk. As I said, I crossed the border illegally hidden in a big bag. It was worth the risk - I went to document the Belarusian revolution of 2020. Like many people, I believed that if the majority took to the streets, it would be possible to fight the dictatorial regime. I remember the women with red-and-white flags, many were even with their children...the Square of Change, where the protest mural was destroyed by the police in the daytime, and restored by the protesters at night. Prayers in church for freedom and peace...late night conversations in the kitchen dreaming of a better future. I also remember how I used to flee from the police on the streets of Minsk...those big green scary police vans...a suffocating courtroom where workers who had promoted a strike were sentenced. Instead of witnessing the success of the revolution, I witnessed its undoing. In any case, it was an invaluable experience that enriched my artistic research. I realized what would be the main theme of my book The Last Soviet Artist, the tragic gap that exists between the new and old generations.

Victoria Lomasko, The Last Soviet Artist

Victoria Lomasko, The Last Soviet Artist

“At the Frunzenskaya stop, cell phones with water cannons are waiting for us.” “Mom, I didn't think this bridge was so long, I can't take it anymore.” I was returning to Russia on a minibus crossing the border through a swamp, hiding from border guards. Outside the window was a suffocating black sky and muddy water. Inside the minibus people were talking about the fact that Putin could send the Russian army into Belarus to extinguish the revolution. I arrived in Minsk as a graphic journalist, but during this trip I realized that reportage cannot describe the Great History that is beginning again in the post-Soviet space. What is needed here is not journalism, but art. I finished the last chapters of the book in Moscow. I typeset it and sent it to several Western publishing houses. Three weeks have passed and the war in Ukraine has broken out. It became clear that the journey of The Last Soviet Artist was over. A few days later I packed my suitcase and was forced to emigrate. But this is a new journey that has no end yet.