29 October 2024 Internationally renowned artist Victoria Lomasko (1978) and a well-known dissident voice from Russia, created an impressive work of art as 'Artist in Residence' at Masereelfonds. Lomasko, known for her graphic novels, political cartoons and murals, was forced to flee her country in 2022 after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Her work sharply challenges inequality and oppression, and highlights voiceless and marginalised communities. Her visually powerful books Forbidden Art, Other Russias and The Last Soviet Artist have earned her international recognition. Her work has been exhibited in various museums in Europe and in 2022 she was invited to Documenta in Kassel. Her courage to tackle critical topics was recognized with the Prize for Artistic Courage at the Angoulême Comics Festival in 2023.

It is no coincidence that Masereelfonds commissioned her to create a work of art. Just like graphic artist Frans Masereel, who created social awareness with his art in the 20th century around themes such as inequality, war, resistance and activism, Lomasko also uses her art to make a statement about the social injustices of her time. Both artists use art as a weapon against injustice.

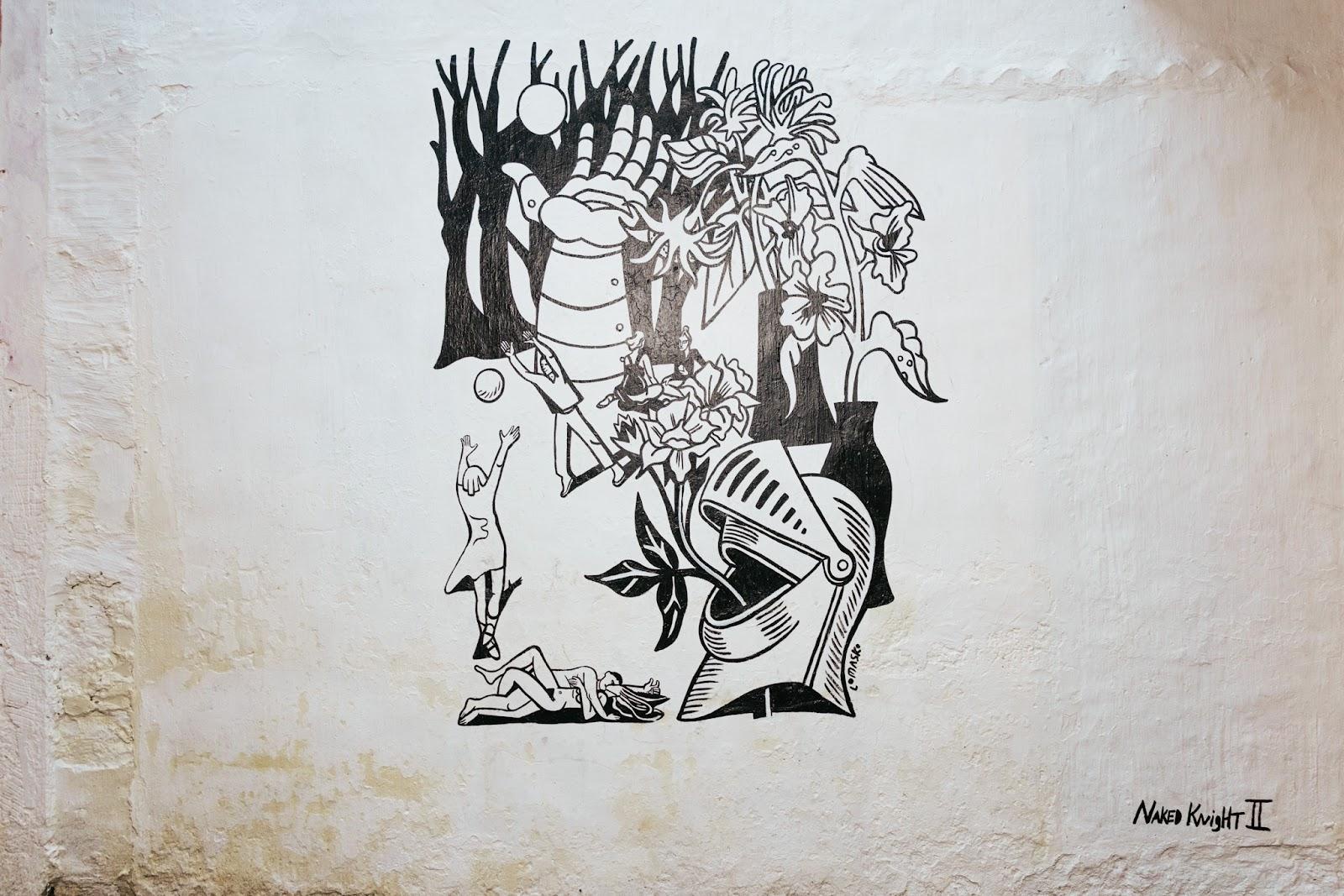

During her residency at Masereelfonds, Lomasko completed a diptych of murals entitled The Naked Knight. The work, which depicts both the political horror of the present and a desired future, can be viewed freely from 12 October at 't MaZ, the new location of Masereelfonds in Ostend.

Victoria Lomasko as a bridge between generations

In her latest book, The Last Soviet Artist, Lomasko explores the generational conflict in the post-Soviet space. This theme, which runs like a thread through the book, concerns the clash between the older generation that grew up under the Soviet regime and the younger generation that has come of age in the modern Russian dictatorship.

Lomasko, who was born in the USSR and experienced its collapse as a teenager, sees herself as a bridge between these generations. Her work reflects the struggles of both groups, understanding the traumas of the past while feeling the disappointments of the new generation.

Lomasko calls herself The Last Soviet Artist because she represents the last generation that remembers the Soviet Union. Her age and experiences allow her to understand both the world of her parents and grandparents, who grew up in the Soviet Union, and the new generation that only knows the modern Russian dictatorship. This experience allows her to develop a unique artistic voice that speaks to both the traditions of the past and the challenges of the future.

Lomasko’s work reflects not only her own memories of the Soviet Union, but also the lives of the people she depicts. She gives voice to marginalized groups such as sex workers, prisoners, truck drivers, LGBTQ+ communities, and political protesters. These groups are at the heart of her artistic message. She gives a face to "the invisibles", the ordinary people who defend the rights of the Russian people. She believes that by portraying the humanity of these everyday heroes, she bridges the gap between the concept of a “hero” and the viewer. She shows them respect and compassion in a society that often ignores them.

Artistic background and personal influence

Victoria Lomasko comes from an artistic family. Her father served the state by making propaganda murals for factories, while at home he painted critical works about the Soviet regime, which he was never allowed to show in public. This dual reality of submission to the state on the one hand and criticism in the private sphere on the other, deeply influenced Lomasko's view of art and her role as an artist. Instead of toys, Lomasko received art materials as a child, because her father hoped that she would realise the artistic ambitions that he himself had never been able to realise.

The Road to Naked Knight : Lomasko's Evolution as an Artist

She began her career as a graphic journalist, documenting the lives of ordinary people on the periphery of Russia. In her work A Trip to Minsk, part of her book The Last Soviet Artist, she captured the protests and repression in Belarus in 2020, a turning point in her artistic approach. During her stay in Minsk, she witnessed mass protests against the Lukashenko dictatorship.

"As a graphic journalist in Minsk, I documented the transformed city decorated with protest symbols, the mass demonstrations and the trials of demonstrators. I interviewed the most activist demonstrators and later realised that they were all women, the leaders of the revolution," said Lomasko. The revolution was quickly crushed by brutal state repression. Thousands of protesters were arrested, tortured, and many disappeared or were murdered. "Rebellion and revolution do not work in a dictatorship. Neither posters nor peaceful protests are feared by dictators." This harsh conclusion has had a lasting impact on her artistic vision.

Victoria Lomasko, Naked Knight II, 2024. @Michiel Devijver

From Graphic Reportage to Symbolic Art

Lomasko experienced the limitations of making graphic reportage in real life. While useful for capturing reality, she found it inadequate to understand events from a historical perspective and translate them to a wider audience. This realisation prompted her to take her art to a more monumental format, filled with symbolism. Her impressive murals not only show how she pushes the boundaries of traditional painting, but also offer new ways to communicate her political message on a larger scale.

She calls the diptych The Naked Knight an attempt to go beyond the traditional approaches of classical political art. Inspired by Frans Masereel, whose work she encountered as a child at school, she uses symbolism in her work, just like him, "something that is missing in contemporary political art", according to Lomasko. "In Naked Knight I break through the stereotype of the traditional political artist who calls for street protests, and I call for the imagination of a desired future," she says.

The symbolism in Naked Knight draws on her experiences in Minsk, where peaceful resistance was ultimately discouraged by violence. Like Masereel, who symbolised his era through images of social struggle and political upheaval, Lomasko attempts to capture the challenges of the 21st century with a new form of symbolism.

The Role of the Political Artist: From Activism to Imagination

Earlier this year, she reflected on the role of the political artist in the 21st century through Liberation (2024), a work commissioned by Milo Rau, former artistic director of NTGent and current director of the Wiener Festwochen: "Is documenting protest political art? Is protest an effective means of changing political systems? Or is it theatrical frustration without impact?"

According to Lomasko, many of the things we adopted from the 20th century to change political systems, such as activism, are no longer effective. “"As a political artist, I can help people free themselves from the black-and-white images that sow hatred," she says. Since her time in Europe, she has noticed that much of the contemporary art on display in galleries is either too commercial or too activist, focused on reflecting the latest news. She argues that there is a lack of symbolic art that reflects the challenges of the 21st century. She believes that this is because many contemporary European artists do not have direct experience with major historical traumas such as war and dictatorship, as is the case in many non-Western countries.

A cocoon of transformation

Lomasko’s exhibition Cocoon at Edel Assanti (London, 2023) explores these themes of personal and societal transformation in times of great historical events. It reflects on the fate of the individual in a world transformed by catastrophes. The "cocoon" to which the exhibition refers symbolises the old form of the world from which something new emerges.

Lomasko sees the world’s transformation in two ways: as a destructive flood or as the wings of a beautiful butterfly that help us fly. "We choose how we perceive the new," she says, emphasising that the future is not fixed and is shaped by everyone. With her work Naked Knight in Ostend, Lomasko not only pays a beautiful tribute to an artist who inspired her, but also continues a tradition of socially engaged art that transcends reality and challenges us to think about the future. Like Masereel did a century ago, Lomasko uses art to symbolise and depict the complexity of human experience and social injustices. This makes her work, like Masereel’s, timeless and universal.

"I was born in 1978 and I remember the last decade of the Soviet Union quite well. I was old enough to love Grandpa Lenin and to be excited about my 'Child of October' badge, a star with his image on it. But by the time I was admitted to the Young Pioneers, I already knew – like all my classmates – that only formal adherence to the rules was expected, and there was no enthusiasm or initiative.

My father worked for many years as an agitprop artist at the secret Metalworkers' Factory. He drew dozens of Lenins on posters and wrote hundreds of slogans, although he never joined the Communist Party. As a child I loved looking at the scrapbook of newspaper clippings he used for his work; pictures of revolutionaries and communists, workers and peasants, hammers and sickles, Soviet women. There was a fixed canon for everything, just like in icon painting. Agitprop artists in the 1980s served the system by mechanically copying these symbols. I was convinced that depicting "revolution" was the most boring thing on earth.

In 2011, when thousands of people gathered in Moscow to demonstrate against the government, I lived in the capital and joined the protests. I felt part of this indignant collective body, a first hint of revolutionary potential. Since then, I have been drawing during demonstrations and protest actions, studying the revolutionary graphic art of revolutions of 1905 and 1917. I am interested in the moment of change, when artists have to create new visual forms, new heroes and slogans, and also the moment of stagnation of the system, when the 'new' turns into a collection of clichés."

Victoria Lomasko