IT’S THURSDAY EVENING of Gallery Weekend 2025—during which 126 London galleries would throw open their doors to remind us that artworks can be seen, and sold, in places other than the Frieze Art Fair—and I’m power walking through Mayfair to catch the tail end of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s exhibition preview at Stephen Friedman. This mini retrospective was the first UK solo show of the late artist, who passed away earlier this year. The opening room contained my favorite works: large, mixed-media canvases that could be compared to peers like Robert Rauschenberg, but which depict a more direct confrontation with America’s past. “Long Live the Resistance,” reads a collaged newspaper headline, pasted like a footnote to the bottom of a large piece called I See Red: Indian Drawing Lesson, 1993. Made shortly after the five hundredth anniversary of Christoper Columbus’s arrival on Smith’s ancestors’ land, this newspaper clipping has acquired a whole new meaning in today’s America.

After twenty minutes or so we were ushered through the streets of London’s West End and onto dinner at Soho House. Champagne was served, mingling occurred, and Smith’s son, the artist Neal Ambrose-Smith, worked the room with a Polaroid camera. I chatted to Stephen Friedman for around five seconds before we were seated at a very long table. I was positioned in Siberia this evening, but luckily Siberia was full of interesting people: the designer Michael Stukan from JW Anderson to my left, and British Vogue’s Olivia Allen to my right. At around 10 p.m. Allen sneaked off to collect her pet Chihuahua from its dog sitter (could there be a more Vogue way to exit a dinner?). I spent the remainder of the night chatting to Elizabeth McLean from Edinburgh’s Fruitmarket Gallery, where a Smith retrospective will open later in the year.

At noon the next day my boyfriend Eric and I were at Thaddaeus Ropac for a talk between Jordan Casteel and the Royal Academy of Arts’ Tarini Malik. The event took place inside the gallery’s front room, where three of Casteel’s recent paintings were on display. Ropac senior global director Julia Peyton-Jones was trying to usher people down to the empty seats at the front, but she needn’t have worried, as soon enough every square inch of space was filled with attendees including writer Charlie Porter, who’d bagged a decent seat in the middle. I was standing at the back and couldn’t really see, so instead I peered up at a portrait of a mother and child called Elizabeth and Roman II, 2025. Luckily, Casteel is a great talker as well as a great painter; she discussed the early days of her career and her efforts to build community in the Hudson Valley. After the talk, we took a discreet elevator up to Thaddaeus Ropac’s private London apartment for a gallery lunch. Ropac always puts out a generous spread, and we loaded up our small Andy Warhol–branded plates with food and took a seat on a sofa next to the writer Francesca Gavin.

We then bussed it over to East London to link up with a press group who’d been touring the galleries since Thursday. The attendee numbers had apparently dwindled today, possibly due to hangovers from the previous night’s dinner (there was talk of very strong shots made with pickled-onion juice). One of the journalists committed the faux pas of asking a gallery staff member how much a work cost; maybe their readers over in Europe needed to know there was a sculpture in London that could be theirs for forty-five thousand euros. Kate MacGarry was showing rubber sculptures by Francis Upritchard: The figurative works looked like gangly, mummified corpses, but since some were playing instruments and others giving piggybacks, it’s clear these creatures––dead or alive––know how to have a good time. Over at Emalin on Holywell Lane, Augustas Serapinas had used the huge glass windows to turn the space into a makeshift greenhouse. Potatoes, beetroot, and onions were growing in long pots made out of scorched wood; at the end of the show’s run, Serapinas will use his crops to make his own cold borscht recipe.

At 5 p.m. I met up with Herald St’s Laurie Barron at their Museum Street space, where the front room was full of Nicole Wermers’s never-ending cat tails, each of them running across the floor before winding into garden hose wheels. Through the back there was a gang of Wermers’s deadpan clay sculptures depicting Victorian ladies in various theatrical states of fainting, their dresses just big hunks of fingered clay. The thought occurred to me that I’d probably end up passing out like that if I attended any more packed-out artist talks this weekend; a friend told me that she’d once been at a performance in a tiny, claustrophobic gallery space and suddenly found herself sliding down the wall toward the floor.

We headed over to Hyde Park for the official LGW cocktail reception, held in the Serpentine Gallery’s new summer pavilion, designed by Marina Tabassum, which thankfully had lots of fresh air. Joining us was Joe Bobowicz from The Face and his cousin Will, who was down from Manchester and has absolutely no involvement in the art world, which was refreshing: He was the only person I met this weekend who didn’t ask if I was going to Basel. I bumped into the lovely Meg Molloy from Josh Lilley Gallery, who is also the founder of Working Arts Club, a networking group for working-class people in the art world (yes, some of us are around). She’d requested I wear one of my many South Park ties to this glitzy event, and I hadn’t disappointed: Tonight’s design featured a recurring image of Stan Marsh vomiting.

IT’S THURSDAY EVENING of Gallery Weekend 2025—during which 126 London galleries would throw open their doors to remind us that artworks can be seen, and sold, in places other than the Frieze Art Fair—and I’m power walking through Mayfair to catch the tail end of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s exhibition preview at Stephen Friedman. This mini retrospective was the first UK solo show of the late artist, who passed away earlier this year. The opening room contained my favorite works: large, mixed-media canvases that could be compared to peers like Robert Rauschenberg, but which depict a more direct confrontation with America’s past. “Long Live the Resistance,” reads a collaged newspaper headline, pasted like a footnote to the bottom of a large piece called I See Red: Indian Drawing Lesson, 1993. Made shortly after the five hundredth anniversary of Christoper Columbus’s arrival on Smith’s ancestors’ land, this newspaper clipping has acquired a whole new meaning in today’s America.

After twenty minutes or so we were ushered through the streets of London’s West End and onto dinner at Soho House. Champagne was served, mingling occurred, and Smith’s son, the artist Neal Ambrose-Smith, worked the room with a Polaroid camera. I chatted to Stephen Friedman for around five seconds before we were seated at a very long table. I was positioned in Siberia this evening, but luckily Siberia was full of interesting people: the designer Michael Stukan from JW Anderson to my left, and British Vogue’s Olivia Allen to my right. At around 10 p.m. Allen sneaked off to collect her pet Chihuahua from its dog sitter (could there be a more Vogue way to exit a dinner?). I spent the remainder of the night chatting to Elizabeth McLean from Edinburgh’s Fruitmarket Gallery, where a Smith retrospective will open later in the year.

At noon the next day my boyfriend Eric and I were at Thaddaeus Ropac for a talk between Jordan Casteel and the Royal Academy of Arts’ Tarini Malik. The event took place inside the gallery’s front room, where three of Casteel’s recent paintings were on display. Ropac senior global director Julia Peyton-Jones was trying to usher people down to the empty seats at the front, but she needn’t have worried, as soon enough every square inch of space was filled with attendees including writer Charlie Porter, who’d bagged a decent seat in the middle. I was standing at the back and couldn’t really see, so instead I peered up at a portrait of a mother and child called Elizabeth and Roman II, 2025. Luckily, Casteel is a great talker as well as a great painter; she discussed the early days of her career and her efforts to build community in the Hudson Valley. After the talk, we took a discreet elevator up to Thaddaeus Ropac’s private London apartment for a gallery lunch. Ropac always puts out a generous spread, and we loaded up our small Andy Warhol–branded plates with food and took a seat on a sofa next to the writer Francesca Gavin.

We then bussed it over to East London to link up with a press group who’d been touring the galleries since Thursday. The attendee numbers had apparently dwindled today, possibly due to hangovers from the previous night’s dinner (there was talk of very strong shots made with pickled-onion juice). One of the journalists committed the faux pas of asking a gallery staff member how much a work cost; maybe their readers over in Europe needed to know there was a sculpture in London that could be theirs for forty-five thousand euros. Kate MacGarry was showing rubber sculptures by Francis Upritchard: The figurative works looked like gangly, mummified corpses, but since some were playing instruments and others giving piggybacks, it’s clear these creatures––dead or alive––know how to have a good time. Over at Emalin on Holywell Lane, Augustas Serapinas had used the huge glass windows to turn the space into a makeshift greenhouse. Potatoes, beetroot, and onions were growing in long pots made out of scorched wood; at the end of the show’s run, Serapinas will use his crops to make his own cold borscht recipe.

At 5 p.m. I met up with Herald St’s Laurie Barron at their Museum Street space, where the front room was full of Nicole Wermers’s never-ending cat tails, each of them running across the floor before winding into garden hose wheels. Through the back there was a gang of Wermers’s deadpan clay sculptures depicting Victorian ladies in various theatrical states of fainting, their dresses just big hunks of fingered clay. The thought occurred to me that I’d probably end up passing out like that if I attended any more packed-out artist talks this weekend; a friend told me that she’d once been at a performance in a tiny, claustrophobic gallery space and suddenly found herself sliding down the wall toward the floor.

We headed over to Hyde Park for the official LGW cocktail reception, held in the Serpentine Gallery’s new summer pavilion, designed by Marina Tabassum, which thankfully had lots of fresh air. Joining us was Joe Bobowicz from The Face and his cousin Will, who was down from Manchester and has absolutely no involvement in the art world, which was refreshing: He was the only person I met this weekend who didn’t ask if I was going to Basel. I bumped into the lovely Meg Molloy from Josh Lilley Gallery, who is also the founder of Working Arts Club, a networking group for working-class people in the art world (yes, some of us are around). She’d requested I wear one of my many South Park ties to this glitzy event, and I hadn’t disappointed: Tonight’s design featured a recurring image of Stan Marsh vomiting.

I stayed for another hour until Stephen Friedman’s Bella Bonner-Evans said she had an Uber heading back to Central and offered me a ride. We tried to catch the tail end of the Toe Rag magazine launch party at Plaster HQ, but by the time we arrived, the doors were shuttered. A huge crowd of bright young things were still spread out across the road, so I got a round of drinks from a nearby pub and the mingling continued a bit longer. My evening ended with what is becoming a Gallery Weekend custom: a cheeseburger at the Five Guys in Piccadilly Circus.

I spent my unscheduled time on Saturday going around galleries by myself in the rain, appreciating that the quality of the shows was much better than last year. The most ambitious exhibition I saw was Philippe Parreno’s “El Almendral” at Pilar Corrias, where a screen fit for a multiplex was showing live-streamed footage from the Tabernas Desert, in the Almería region of southern Spain. In order to own the work, you basically purchase the land (comprising thirty hectares), and the stationed, unmanned (but moving) cameras go into operation whenever the work is exhibited. This is the kind of complicated art I would permanently install in my living room: Who needs a Netflix subscription when you could have a multi-angle live movie of an almond grove in Spain?

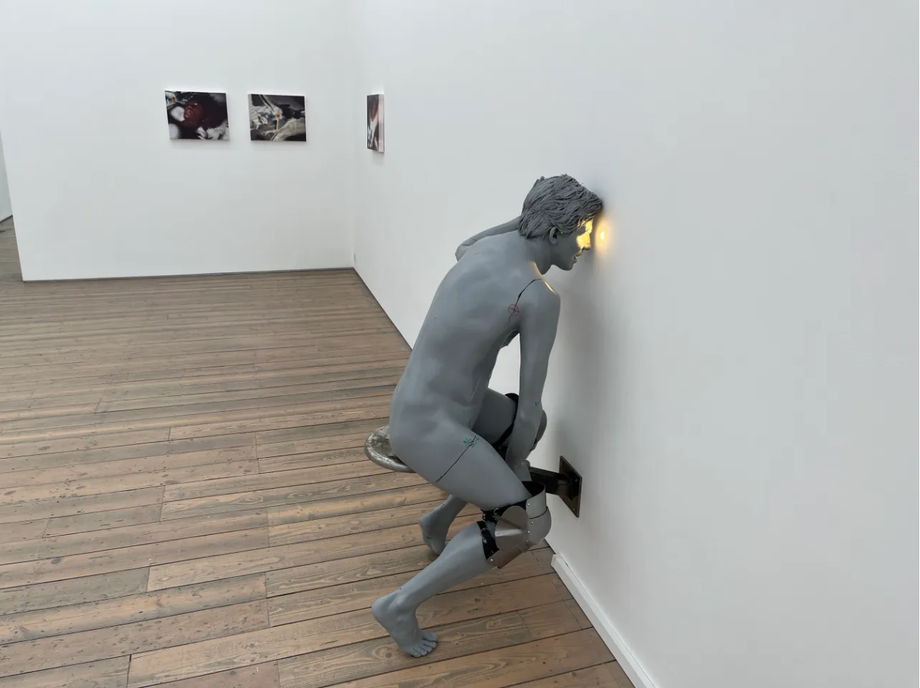

Around the corner at Massimo de Carlo there were ten grayish portraits of Francis Bacon by Yan Pei-Ming, one of them based on a stolen painting of Bacon by Lucian Freud. I couldn’t help but wonder what Bacon himself would have thought of the works, given his legendary dismissive opinions of other artists. Edel Assanti had a solo exhibition by Simon Lehner called “Of Peasants & Basterds.” Someone told me that the show—based around incels—was “very me.” I’ll take that as a warped compliment, and actually, they were correct: The naked, breathing animatronic mannequin that looked like Patrick Bateman did indeed seduce me. A 3D-printed silicone sculpture of the word “community” greeted visitors to the gallery, but inside most of the work made me think only of men doomsurfing alone at home. A large canvas called White Knight I, 2025, depicted another male figure: face obscured, but with a body rendered to signal both a medieval soldier and a fascist politician. Stepping back from the piece revealed giant fingerprints, the kind left on smartphone screens after a heavy session on X.

I next headed to Farringdon for Judith Dean’s exhibition at South Parade, one of my favorite painting shows of the weekend. It just so happened I’d stumbled into a walkthrough with the artist, which felt more like a good old-fashioned art school crit (there was at least one undergrad in attendance keen to ask questions). I mentioned to dealer Isaac Simon that I’d been intrigued to see the exhibition after reading a review by the critic Pierre d’Alancaisez, who had given it a very rare four stars (I concur!). It had been raining pretty hard all day, but I decided to do one last stop at Ginny on Frederick, where a loyal art crowd hadn’t let the bad weather deter them from the opening of Okiki Akinfe’s exhibition “Where the Wild Things Are”: The show was packed, with a pile of umbrellas stacked up near the beer bucket. All I managed to get a peek at was a trippy-looking painting of some cows, it being one of those busy private viewings where you have to go back again to appreciate the work. It’s on my to-do list.

Sunday was sunnier and brought another jaunt east. Victoria Miro had a sprawling fortieth-anniversary show, my favorite piece being a small Elmgreen & Dragset work, Still Life (Bullfinch), 2024, a pair of white hands cupping a breathing animatronic bird (animatronic breathing seems to be a thing at the moment: like Jordan Wolfson, but more Zen). Down in Three Colts Lane, I loved the strange little paintings by Anna Jung Seo at Project Native Informant: Some of the portraits depicted human forms that looked like blubbery versions of a Hans Bellmer doll. Maureen Paley was showing Kayode Ojo . . . but you’ll have to stay tuned for my upcoming review. Across the street at Rose Easton, visitors were invited to grab a footstool and join in on the Jungian libido-fueled fun of Amanda Moström’s exhibition; a sculpture titled Brooding, 2025, involved horsehair suspended from the ceiling, with space cut out for visitors to perch under. A 3 p.m. performance by Michael Dean took place next door at Herald St—again, this was so mobbed I couldn’t see, but images on Instagram showed the artist lying face down on the floor. Bonner-Evans turned up to see the performance with a friend and was stunned to learn it was already over by 3:09. Too late, hon: This one was short and sweet.

Up the road we visited Neven, where dealer Helen Neven was vaping and drinking a can of Diet Coke left over from the show’s private view a few nights before. I wanted to catch this exhibition by Katie Shannon, titled “DEVOCORPOSTO,” as the subject matter was close to home, literally. Shannon’s works were centered on her hometown of Cumbernauld, a Brutalist postwar burg in Scotland (much of its town center is due to be demolished) near where I grew up. A line of shirts and ties (purchased from a supermarket) were mounted on the wall, based on a shirt-themed mural from a Cumbernauld underpass—the dimly lit kind where teenagers cut class to smoke. Elsewhere, a drawing shows a girl smoking and drinking in a nightclub, based on a distorted photo Shannon took the year before an indoor smoking ban came into effect in Scotland. Even at the age of thirty-five, I’m still too young to remember those glory days of coming home from a night out stinking of other people’s cigarettes.

Over at the Approach, we found artist Peter Davies chatting to visitors at “Kind of . . . ,” his dual exhibition with Mary Ramsden. We had a lovely conversation about Willem de Kooning, Paul McCarthy’s legendary video work Painter, 1995, and Davies’s own move from large abstract paintings into the small still lifes exhibited in the show. These recent works look like crochet but are in fact color grids carefully executed in pencil and acrylic. He even made a tiny version to hang as a decoration on Ginny on Frederick’s Christmas tree last December. It had been a while since I’d had a decent chat with someone about painting. Cheers, Peter!

The Approach gallery is upstairs from the Approach pub, so we had a quick pint before taking the long journey to North Acton for a six-gallery closing party hosted on the rooftop of Sherbet Green’s space. Citymapper sent us along a creepy footpath full of rats and used condoms. It was worth the trek—the only proper party I’d attend the whole weekend, a rooftop bar with DJs, a big crowd, and zero formality. We attended one final artist talk with the Moscow-born Sonya Derviz, whose work had a double Gallery Weekend outing: a solo show here at Sherbet Green, and a two-person show with Joel Wycherley at nomadic project space Soft Commodity, which was being hosted by the Shop at Sadie Coles. Afterward we headed back up to the party, joined by our friends Evgeniy and Marat, where we also hung out with artist Li Li Ren. Gallerist Mazzy-Mae Green was the perfect host, interacting with guests and occasionally hopping behind the bar.

There were still dozens of shows I hadn’t seen. For LGW 2026 I propose that the galleries stay open all through Saturday night. (Stumbling into Ugo Rondinone’s “rainbow body” exhibition at Sadie Coles HQ at 4 a.m. would have been something truly special.) Several people had recommended I catch Glasgow-based Kialy Tihngang’s exhibition “Icyyy Grip” at Studio/Chapple in Deptford; this is only a short walk from my house, but I’d missed it. However, it just so happened that Louis Chapple, who runs the space, was DJing. He offered to open the show for me on Monday, bless him, and so my weekend spilled over into Monday afternoon with very sobering work examining the harrowing form of mutilation known as “breast ironing,” a practice found in Cameroon, where the artist still has family. Rather than go for a grim documentary format, Tihngang had created a pop-saturated girl’s bedroom environment, borrowing the language of beauty-product advertising to showcase her “flattening suit,” which the gallery text explains is “a wearable tool designed to compress the breasts through speculative technological or magical activation.” What Tihngang seems to be exploring is how the language of the beauty industry often normalizes insidious forms of “cosmetic treatments,” from high-risk plastic-surgery procedures to so-called “skin-lightening creams.”

While the curators who were in town had made the effort to check out smaller galleries such as this, I heard the same old story about collectors not really venturing so far. It’s a shame, as these are always the best places to discover new work by younger artists; perhaps we should begin referring to Deptford, or Acton, or Harlesden, simply as “Downton Belgravia.”