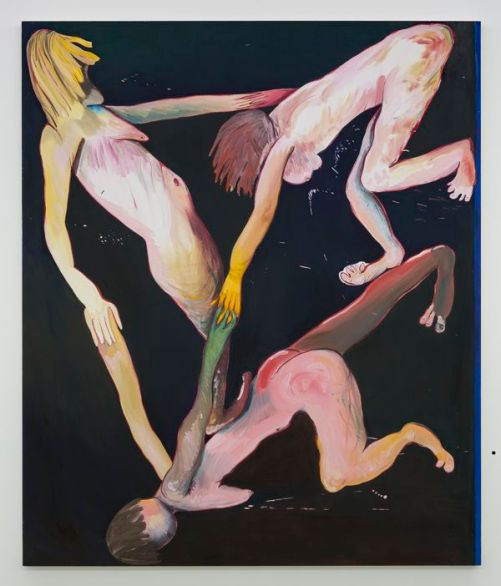

15 August 2018 Emma Cousin’s exhibition, Mardy, at the Edel Assanti gallery, marks a turning point not just for the artist’s career but also for the audiences’ understanding of art itself. The exhibition consists of four large-scale paintings, each housing three to five female figures. The female figures are entangled, sometimes pushing or pulling at each other’s body parts, sometimes pointing as if to compare their own body with another’s. Cousin is already known for her unique use of body parts, and elsewhere in an interview she tells us about the function of bodies in her art:

"I'm curious about our expectations of our bodies and judgements of other bodies. I'm testing their limits and interested in putting the bodies at risk. They exist in a liminal space which is a place of discomfort, an edge or a boundary. A space between us and not us."

Hot Ribena, Oil on canvas, 190 x 255cm

Yet this exhibition seems to differ from Cousin’s previous works with their surrealist humour and puzzling levities. This time, the body is not just a liminal space for exploration of identity, but a space that points and is pointed at, that suffers and causes suffering. Whilst the list of artists sending out the message of body-positivity is growing, Cousin directs a multi-layered criticism at the ideals that have been forced upon the female gender and the grave consequences such an imposition has for female consumers-cum-viewers. In this sense, Cousin’s Mardydelivers dissident disturbances upon the very fundaments of art and artistic tradition. By capturing the essence of comparing and despairing, of pointing and subsequent maiming, she brings the interaction of art with its audience to a cul-de-sac of dissatisfaction and disappointment. The female body has always been maimed in its male idealised form: from the unkind and misogynistic artistic expressions of ancient cultures such as Greece and Rome, where female bodies and faces were standardised by men, as in the divinities and victims of divine abductions; to the fetishised angels and saints of medieval paintings; to the Renaissance resuscitation of the Graeco-Roman male-idealised images of women, until perhaps the rise of modernism and its fragmentary representations (and even then, the fragments point to an unreal conception of the female figure). And when these bodies transgressed the male gaze and became overweight, hirsute, old, or ‘dis’-figured, they were demonised and monstrified.

Throughout its existence the female body has been ‘maimed’ and ‘maiming’: ‘maimed’, for the artists must have run with knives carelessly cutting through the population, ignoring the reality of the variety of female bodies, despising the validity and aesthetics of ‘deformities’ and ‘malformities’ which the artists have exiled to the invented boundaries of ‘de’s and ‘mal’s and ‘dis’s, in order to finally arrive at a figure that is maimed for the artist’s pleasure and the audience’s joy; ‘maiming’, for an idealised image has been putting female bodies under severe pressure, enforcing the notion that gloria, fama, love, and company, come to those women who can live up to this able-bodied and idealised image. In this sense, Cousin is a chronicler of wars and battles that artists and a tradition of imagination and taste have declared on the female audience, and in which the female has remained the usual, desired casualty.

Perhaps at first sight one might conjecture that there would be no room for Cousin’s usual humour. Cousin’s surrealism is not a detachment and departure from reality, but an extraction of travesty and tragedy from reality, in which the acts of pointing, reflecting, identifying and idealising have led to otherification, maiming, and a mass-scale enterprise of mental and physical health issues. ‘Mardy’, the powerful adjective for moodiness and instability, that in artistic and popular tradition, from Hesiod’s likening of women to the sea in their instability and evilness, to the medieval witch-hunts of women, to the thousands of hysterectomies and clitorectomies performed on women who developed neuroses by ‘living’ in an oppressive Victorian age, has been assigned time and again to the mental state of female bodies—bodies that are essentially and constantly damaged by the anxiety of having been compared to an unreal, unethical ideal. ‘Mardy’, as an exhibition and as an adjective, is Cousin’s piling of jokes on jokes, and letting the ‘humour’ of the situation interact with itself, till the gory reality gushes out of it. The distasteful joke, the circular machina mundi of the enterprise of creating anxiety and forcefully thrusting female individuals into a harmful situation, and then blamelessly standing aside and watching them endlessly and blindly navigate through the situation and their own bodies, is skilfully personified in the circular and claustrophobic interaction of female figures with no eyes.

This exhibition by Emma Cousin is self-referentiality of the highest order. Each element of Cousin’s artistic past is bent into convoluted circles to become a self-referential soliloquy. The artist’s catalytical technique is emphasised by her depictions of actions in liminality: arms at the threshold of dislocations, breasts on the brink of being ripped, necks on the verge of breaking. Nothing is dislocated, yet everything signifies maiming and disjunction of the subject matter, the method, and the operative modes of life—the whole machine is broken. Cousin truly captures the tragic reality of body-consciousness and the subsequent life-crippling anxiety and dysmorphia caused by societal and artistic norms and ideals. This is one of the finest catalytical engagements with artistic imagination, revealing what artists have done to art and what art has done to its audience.

Perhaps one could return to Bracken and Brown Adders to end (or start) this exhibition with. The painting depicts an easier and earlier stage of childhood, where bodies are more disconnected and more content with solitary activities, yet still disturbed, still vibrating with a dull anxiety of learning to point, of being forced to learn to maim.

This exhibition is successfully presented by Edel Assanti. Located in Fitzrovia and minutes away from the bustle of Oxford Street, the gallery is a space for multidisciplinary artists who engage with reality in all its forms and manifestations. The staff are friendly and well-informed. The gallery is well-lit and it allocates a large amount of space to each artwork.