The American artist and musician redeems humanity’s junk and reveals the dark histories of mundane objects

Lonnie Holley: All Rendered Truth, Installation view, Camden Art Centre, 5 July - 15 September 2024. Photo: Rob Harris

When Lonnie Holley (b1950) begins to sing, the world seems momentarily lighter. Holley plucks thoughts and phrases from his memory and spins them out into spoken word poems that combine the earthiness of the blues with the loftiness of hymns. Musicians – sometimes his own backing band, sometimes guests – improvise soundscapes around his words, covering a sonic range from tinkling folk to thundering post-rock. But Holley’s unparalleled voice, grizzled, richly patinated, lancing between whisper and shriek, is the anchor and the stern.

Holley performed at Camden Art Centre on 5 July, to mark the opening of his exhibition. He ended his set imploring the audience to repeatedly scream – for political change, for climate security, for an end to prejudice, as well as for personal joy. Everyone joined in, at first timidly, eventually full-throated. When Holley stood up towards the end of the song and raised his hands in a thumbs-up gesture, we involuntarily followed, led along by his preacherly charge. One friend told me afterwards that she felt spiritually cleansed.

Lonnie Holley: All Rendered Truth, installation view, Camden Art Centre, 5 July —15 September 2024. Photo: Rob Harris.

Holley has lived a truly remarkable life, like the protagonist of a picaresque novel. He was born in Birmingham, Alabama, one of 27 children. His mother left him in the care of a burlesque dancer who would take him on tour. Without much in the way of friends or family, he would wander. After running away from one foster father, he was dragged underneath a car and left in a coma. Eventually, after a spell working on a delivery wagon in New Orleans, aged nine, he was sent to the Alabama Industrial School for Negro Children, effectively a labour camp, a site of torture (an excellent podcast, Unreformed, tells its grim tale). Later, he worked at Disney World in Florida.

Holley’s first artworks were tombstones he carved for his sister’s children, who perished in a fire. It triggered a hobby of making sculpture from found objects, which Holley strewed around a landscape near Atlanta airport. But he did not see the pieces as art until a fireman asked: “Who’s the artist?” Gradually, the art historian Bill Arnett, whose son Matt is now Holley’s friend and manager, promoted Holley’s work. Since the 1980s he has been exhibited at the Smithsonian, the Royal Academy, London, and the National Gallery of Art, Washington DC and has been collected by major institutions and put on permanent display at the United Nations. But All Rendered Truth is his first institutional show in London.

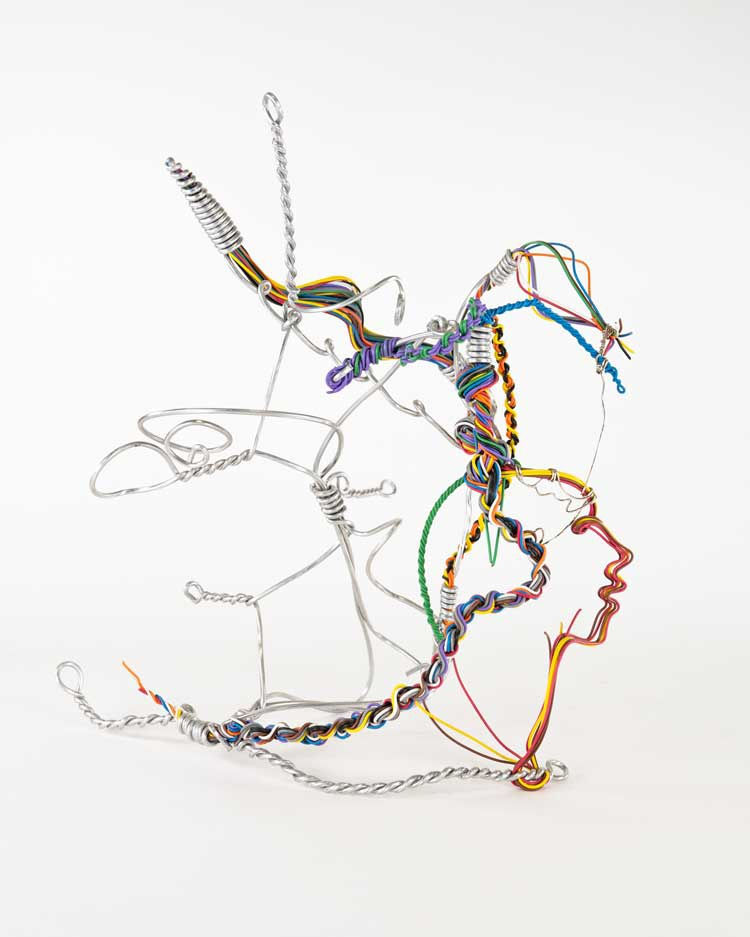

Lonnie Holley. Retreating Her Power, 2001. Electrical wires and wire. © Lonnie Holley. Image courtesy Edel Assanti. Photo: Truett Dietz.

Recorded music entered the picture a decade and a half ago, after Holley repaired an old Casio keyboard. But after seeing him perform, his voice and words seem to emerge from his art. Both take debris – the detritus that is strewn across the US, the stories and items left behind by its people, the travails of Holley’s own life – and reassemble them into works of fragile beauty. Some of Holley’s sculptures remind me of a great American industrial painting, something by Charles Sheeler perhaps, that has been atomised and reconstructed. Yet somehow the sculptures are not unruly. This is not art as an evocation of the scrapyard. It is art as a process of renewal.

Lonnie Holley: All Rendered Truth, installation view, Camden Art Centre, 5 July —15 September 2024. Photo: Rob Harris.

The first gallery at Camden features a swarm of 20 minute sculptures raised on plinths. Holley takes junk – brick, bone, chicken wire, rusted metal, pipe cleaners, heating coils, conglomerate rock and much more – and turns it into glittering treasures. None of these components has ever been so beautiful. Some of them are portrait sketches in wire, contours of faces caught for a moment. Electrical waste – such as wires, circuit boards and heating coils – calls attention to the wastefulness of our present time. Technologies that recently seemed miraculous are now just more garbage. Holley’s transformative works reveal the grace of these objects, while turning them into memorials.

Lonnie Holley. The Nine Notes, 2024. Enamel and spray paint on antique church organ pipes Image courtesy of the artist and Edel Assanti. Photo: Truett Dietz.

Although this exhibition features materials from Britain – a flattened copper pipe from a London road intersection, Victorian glass apothecary bottles, a blackberry bush from Suffolk – Holley’s artistic language is undoubtedly American. He joins a lineage of assemblage artists including Ed and Nancy Kienholz and Robert Rauschenberg. There are also echoes of Jasper Johns’ symbiosis of painting and sculpture. A new work, The Nine Notes (2024), ties together organ pipes with a dusky abstract painting. Each pipe commemorates a victim of the 2015 Charleston church shooting, where a white supremacist opened fire on church members. The painting depicts the soft outlines of faces, drawn together in a sort of congregational limbo. Other paintings in the exhibition depict similar scenes in brighter tones. They have the same communal aspect as his performances.

Lonnie Holley: All Rendered Truth, installation view, Camden Art Centre, 5 July —15 September 2024. Photo: Rob Harris.

Threat and security often intermingle in Holley’s world. Chain Gang: Mt Meigs (2019), named for the site of the Alabama Industrial School, is a spindly ensemble of forks bound together by a padlock. They are oppressed, but have their own sharp points.

Lonnie Holley, Hung Out, 2021. Wooden drying rack, rifle targets, and clothes pins. Image courtesy of the artist and Edel Assanti. Photo: Truett Dietz.

Hung Out (2021) sees shooting targets hung up as if to dry on a clothes airer, violence domesticated. And one of the largest works here, Without Skin (2024), entangles industrial fire hoses with wooden chairs. Holley intends it as a tribute to people who died in racist church burning, and those who fought for civil rights against the forces of authority. The huge hose becomes simultaneously a constricting snake and a life-saving thread. Other artists have teased out the history of abandoned objects, the hidden stories of stuff. But few have captured the knife-edges between tool and trash, hope and fear, life-giving and life-taking. Holley treats remains with the respect they deserve.

Lonnie Holley, Without Skin, 2023. Fire hoses, wooden chairs, and nails. Image courtesy of the artist and Edel Assanti. Photo: Truett Dietz.